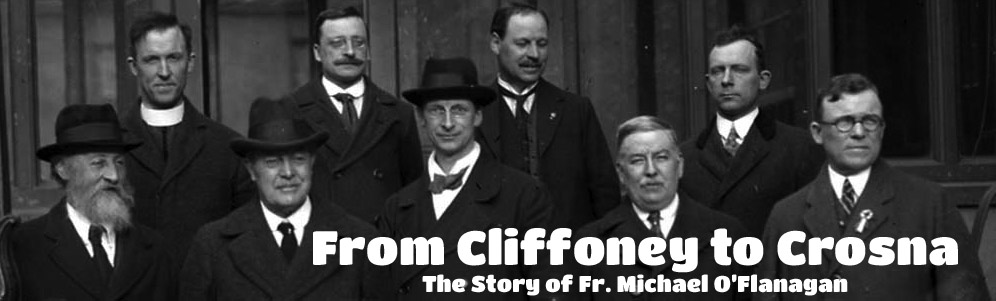

Peace moves, December 1920

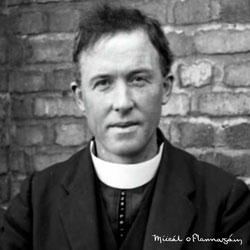

Fr. Michael's efforts to establish some kind of moves towards a peace settlement in December of 1920 caused uproar among his peers, who were swift to denounce him. However, a look at wider events and some newly discovered papers give us an idea of what was going through Fr. Michael's mind when he initiated his series of telegrams to Lloyd George. At the time he was acting head of Sinn Féin, all the other members being under arrest or on the run. A spate of violence in the Autumn of 1920 looked to be spiralling out of control, culminating in Bloody Sunday on November 21st.

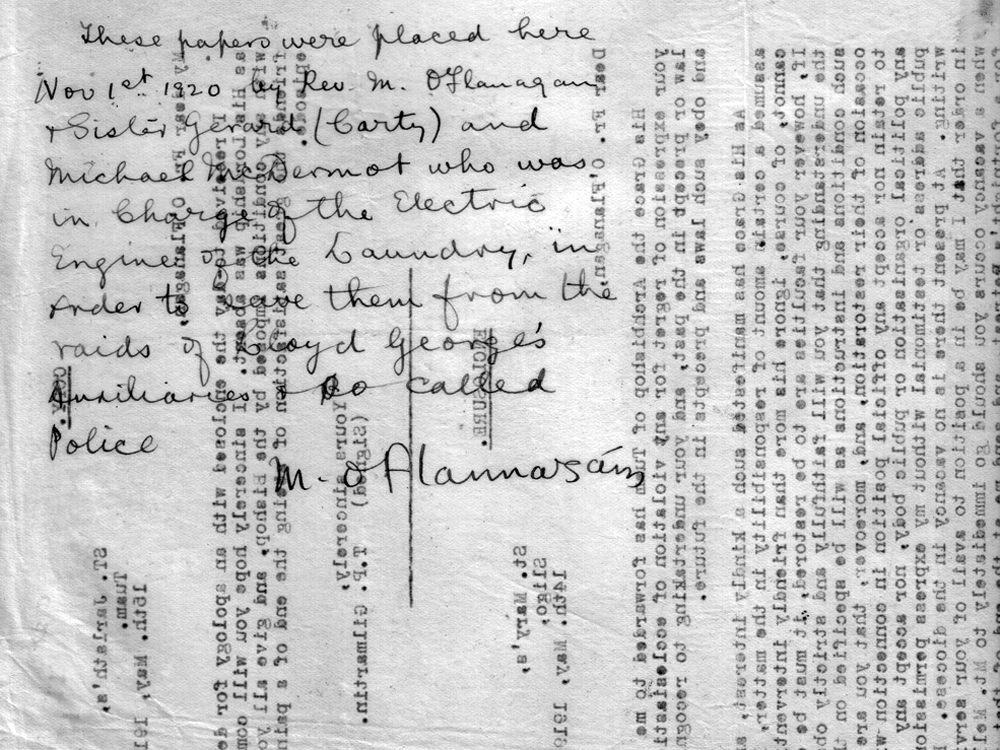

During October when Fr. O'Flanagan was staying in Roscommon,Vera McDonnell, a Sinn Féin stenographer who worked as a typist for Fr. Michael, was witness to the raid on his rooms in Roscommon presbytery on Friday October 22nd 1920, which prompted him to place his papers in Loughglynn Convent for safe-keeping.

The door of the Curates' house was opened by Fr. Carney, the other curate, and the Auxiliaries proceeded to search Fr. O'Flanagan's rooms. They pulled the place asunder and read all his letters. Fr. O'Flanagan was interested in the derivation of Irish place names and, for that reason, he used to buy old Ordnance survey maps at auctions. He had shortly before bought some belonging to the County Surveyor who had died and pieces of these had been cut out apparently by the Surveyor for his own purpose. The Auxiliaries came to the conclusion that Fr. O'Flanagan had cut them out for the I.R.A. for the purpose of attacks on the Crown forces. They told me if they got Fr. O'Flanagan they would give him the same fate as they had given to Fr. Griffin. They also told me to leave the town at once, and that my being a woman would not save me from being put up against a wall and shot. During all this time Fr. Carney remained in his own rooms and was not molested. Vera McDonnell, B.M.H. W.S. - 1,050

Raid on Father O'Flanagan's house.

A raid by two Auxiliary officers accompanied by two R.I.C. Sergants was carried out on the home of Father O'Flanagan. The two R.I.C. sergants were sent to ensure that the Auxilaries would not take away any private porperty. Father O'Flanagan's typist was put under arrest by the Auxilaries and ordered to leave the town in so many hours, and her typewriter seized. During the search the two Auxilaries found a £5 note in a jug on a shelf, which they collected. The two sergants there and then objected, but their objection was overruled by the Auxilary officers.

As they were about to leave they saw a suitcase. They could not open it, so they got a knife and ripped it open. The case contained vestments belonging to the priest. The sergants again objected to the cutting of the suitcase, but without effect. They suggested that the case should be taken to the barracks and held there when it could be opened in the presence of Father O'Flanagan. On opening the case they cut the vestments to pieces.

When Father O'Flanagan returned to his home that night and saw the depredation that had been done, and missed the £5 note from the jug, he became very annoyed. He came up to the Co. Inspector to complain about the matter, but got no satisfaction from him. Later he saw the colonel in charge of the military, but got less satisfaction there. He told them that he would go further with the matter and have an enquiry opened. The Auxilaries, on hearing this, made arrangements to have Father O'Flanagan taken away and probably shot. This came to my knowledge and I rushed down to Father O'Flanagan immediately and asked him to leave his house as soon as possible and that if he stayed in the town not to stay in any house the second night, but to leave town at the earliest opportunity. He took my advice and went to the College in Sligo.

During his time there he prepared a file of everything that had transpired during the raid on his house. He got this away to America and Dr. McDonnell told me that the contents of the file were posted on the doorway of the British Consul's office in America and other public places. As a matter of fact it got so much publicity in this manner that the British Consul communicated with the Home Consul to know if it was true. He communicated with the British Government, who knew nothing about it. They, the British Government, communicated with Dublin Castle and, as the latter knew nothing about it, they sent a convoy of twelve lorry loads of British military down to the Co. Inspector's office in Roscommon, bringing down the dispatch that came from the British Consul in America and asking for a report on the matter. I can't remember what Co. Inspector's reply was, but he sealed it next morning and sent it to the officer in charge of the convoy to have it taken back to Dublin Castle.

That night, with the aid of my skeleton key, I gained access to the Co. Inspector's office and got hold of the file of correspondence dealing with the raid. I copied the complete contents of this file. From this time I knew that an inquiry was about to take place, but as I did not know what the two R.I.C. sergants were prepared to say, I invited them to a local public house for a drink and when they were sufficiently refreshed I discreetly introduced the matter of the raid. I asked them how they were going to act and they said they were looking forward to the day when they could swear to the truth of the Auxiliaries taking the £5 note and cutting up the vestments. I left the original file back in the Co. Inspector's office and handed the file of copied documents to Doctor McDonnell who, in turn, passed the file on to Michael Collins and the latter got the file sent to America where the copied documents were again used as propaganda and posted on the British Consul's doorway together with the original poster about the raid.

John Duffy, member of R.I.C. Athlone, and Kiltoon, Co. Roscommon 1916 - 1921.

The country was at boiling point during the autumn of 1920; on Monday October 25th Terence MacSwiney, Lord Mayor of Cork died after a 74 day hunger-strike and at Moneygold near Ahamlish cemetry an I.R.A ambush killed four of the nine men on patrol from Cliffoney R.I.C. Barracks. Reprisals came swiftly to Cliffoney with a series of savage raids by the Auxiliaries who visited several nights of terror upon the people of north Sligo. The R.I.C. County Inspector reported: "The houses of some leading suspects were burned as well as the Father O'Flanagan Sinn Féin Hall at Cliffoney."

Andrew Conway's brother was a constable who resigned. The house was burned at five o'clock in the morning, and the ex-policeman escaped in his night-shirt. A good deal of the crops has been burned in both places. The Father O'Flanagan Hall is in ruins; the Ballintrillick Creamery is burned, and portion of the Grange Temperance Hall, including the library is also burned.

Weekly Telegraph, November 6th, 1920.Peace essay, December 1920

De Valera is a sane moderate reasonable man. I believe that on the basis of Irish Freedom and English security, De Valera and Lloyd Goerge could arrange a treaty of peace that would be ratified by the overwhelming majority of the people of both Ireland and England.

The (great mass of the) Irish people have no absolute enmity towards England. Their enmity is consequent upon the present oppression. As soon as the oppression ceases, the enmity will cease. It is all moonshine to say that that the memory of past oppressions has got anything to do with it.

The Irish farmer deserves nothing better than a good market for his cattle, his sheep and his pigs. He is willing and able to give good value and he wants freedom to bargain so that he may be able to insist on a good price. He wants to be free to build and run his creameries and put his butter on the English (market or any other) market, in such condition, so that it can hold its own against the best produced in Denmark or anywhere else. If the creameries are destroyed by the servants of the crown, and the Irish farmer has to do without his money, it is poor consolation to him that the Englishman has to do without his butter.

The Irish shopkeeper wants to be free to buy English goods and free to bargain so that he may get them at a reasonable price. Ireland is buying anything up to £150,000,000 worth of English goods every year. If the English merchants are fools enough to allow their servants to continue (buying) burning Irish shops, numbers of Irish shopkeepers will be driven into bankruptcy. The English merchant will lose (his money, and he will) the money that is owing to him, and he will lose his market in the future.

The one predominant impulse in the hearts of all the people of Ireland is the desire for peace — peace within Ireland itself and peace between Ireland and England. War is bad enough and Civil War is the worst form of war. But the war that we have in Ireland is of a new type. What must be the unspeakable horror of the new type of civil war we have in Ireland, untempered and unrestrained as it is, by any of the conventions of a civilised society.

Even the old vocabulary of slaughter is not enough to express the taking of human life. A man is no longer spoken of, as having been killed or murdered or assassinated. No: he is "done in." The man who fires the fatal shot will turn on his heel and say to his "I've got him" just the term used when one shoots a rabbit.

Much of the killing is so mysterious that it is (difficult to guess even the motive) impossible to arrive at any safe conclusion as to the perpetrators or the motive behind the killing, although as a rule, there is little difficulty in deciding the party.

The people of Roscommon hear one day that Jack Conroy has been killed in his home a few miles outside the town. A few days afterwards they hear that Paddy McCormack has been shot in a Dublin hotel. It is (clear) probable enough that one of these men was killed by people who believed that (their action they were helping) they were acting in the interests of the British Empire. It is also probable that the other man was killed by people who believed that they were acting in the interests of Ireland. In any country (enjoying) under a civilised government, machinery would be available for the thorough investigation of these deaths. But in Ireland this machinery has all been scrapped. Not merely is trial by jury gone but the Coroner s inquest is also gone. In the case of poor Conroy, I think even the farce of a military enquiry was dispensed with. The two young men who called to notify the deaths to the military in Roscommon ran the risk of losing their own lives in the barrack yard. This is an example of how government against the consent of the governed is working out in detail in Ireland.

The situation is at present largely controlled by desperate men, men who are naturally desperate or by men who, by the pressure of circumstances have been rendered desperate. On the one side are the forces of England, the RIC, used as the instrument of oppression of their own people. While the people submitted tamely to oppression, the path of the RIC ran smooth. As soon as the people began to assert their their natural right to conduct their own affairs, pressure from Dublin Castle made active the latent oppressive power of the RIC. By this oppression, some of the ardent young men of Ireland were made desperate. They began to hit back. Some of the police were killed. Other policemen (RIC) became conscience stricken and resigned. At first it was easy enough for a policeman to resign. However, it was desperately difficult for a middle aged man who had spent many long years in the force to resign particularly if he had a wife and children dependent on him.

(The government) Dublin Castle began to fill up the ranks with men who had been through the war. They were for the most part, English men. They were of every variety of disposition and character. These were the Black and Tans. It is generally believed in Ireland that many of them had been liberated from jail on condition that they enrolled themselves in the Royal Irish Constabulary. These men and the old members of the RIC got on badly together from the start. Soon they threatened any RIC man with death if he resigned. Some of the policemen in Ireland have been killed by their brother policemen because they were about to resign. Thus the unfortunate policeman finds himself between two fires. If he remains in the force, he must act as guide and helper to the Black and Tans in their campaign of murder and outrage, against his own people. If he resigns and tries to hide or disguise himself, he may be taken for a spy or an Irish Volunteer on the run. If he walks openly he is bound to be assaulted and perhaps murdered by the Black and Tans.

But the most sinister development of all is the formation of the Auxiliary Force. This force consists of ex army officers. They are dressed on English military uniform. This is evidently done for the purpose of rousing the anger of the regular military in case one of them is attacked.

They are not subject to the local authorities either police or military. They take their orders direct from a General Tudor in Dublin Castle. They stay in hotels and pay what they like. They commandeer motor cars and fly here and there throughout the country, scourging, beating, terrorising, robbing, burning and murdering. So obnoxious did they make themselves in (Claremorris) one western town the military there disarmed them. In (Strokestown) another the military drove them out of the town at the point of the bayonet. I refrain from mentioning the names of the towns lest the influence of the General Tudor might be used to penalise the military commandeers concerned.

(At present the policy seems to be to drive) For many months past, the effect of the policy was to (drive) put an ever increasing number of the young men of the country "on the run." When a man is on the run he must hide. He must hide so as not to be recognised by police, military or Auxiliaries. If he is caught, he is in danger of being imprisoned, beaten or killed. He must avoid being recognised by children who have not enough sense to keep their mind to themselves and to the many odds and ends of people who, for one reason or another, are unable or unwilling to keep a secret. Rather than run the risk of involving a kind neighbour to house him, he sleeps out of doors. Hardship soon makes him desperate. He joins a party of men who already have got a few guns. They want one for him. There is no place to get it except from a party of police or military ambushed on the roadside.

The ambush takes place. A few guns are captured. An old score is wiped out. But immediately the whole country is subjected to a reign of terror. Men who had hitherto taken no part in the fight are killed or their homes burned. Others are terrorised and sent on the run. Another ambush is necessary to procure more guns. Therefore, the vicious circle runs its deadly round.

I appeal not merely to the moderate man but to all the sane men of the community on both sides and (on no side) those who have not yet joined either side to make an effort to rescue Ireland and England from this mad orgy.

There is no great difficulty in the way of peace between Ireland and England. Ireland wants freedom. England wants security. A free Denmark is not a danger to England. Neither is free Holland. A free Switzerland is no danger to France. Far less could a free Ireland be a danger to England. A free Ireland could not, even if it dared, be a menace to England. Switzerland, Holland and Denmark guarded their neutrality with jealous care during the war. A free Ireland would guard its neutrality with far more jealousy. For mad as it would have been for Switzerland, Holland or Denmark to join in the war against France and England, it would infinitely be more mad for Ireland. Switzerland, Holland and Denmark could at least get adequate help from Germany. Ireland could get no help. Ireland would be in a position similar to Portugal. Portugal could afford to join in the war on the English side. She could not afford to join on the German side. Still less could an independent Ireland. An independent Ireland, in any war between England and any other country must either remain neutral or join on the English side.

An independent Ireland would not merely keep neutral itself, but it would compel all of its citizens to remain neutral. But a Dublin Castle government from England will never be able to compel Irishmen to remain neutral. Rather will it always produce desperate men, who will be prepared to engage in the most violent and dangerous enterprises against England.

If England wishes to arrange a treaty of peace with Ireland, she must treat with Ireland's chosen spokesman Eamonn De Valera. He is the only man who can speak officially for Ireland. Just as Lloyd George is for the time being the only person who can speak for England, so de Valera is the one man who can speak for Ireland.

Let us in God's name (take) set aside the men whose deeds are desperate, before they have done any more harm. Men who, (will) for their own selfish ends, will burn thirty five creameries today and will try and lay the blame on the Sinn Féiners. They will burn English cotton factories tomorrow, if by doing so they can hope to enhance their own position. Men who murder the Lord Mayor of Cork or Father Griffin for political ends, will murder tomorrow in England – I do not care to mention any of the many names that occur to my mind. All that will be necessary for them is to pick out some one.

LLOYD GEORGE REPLIES TO REV. M. O'FLANAGAN

London: Premier Lloyd George today sent a reply to the recent request by Rev. Michael O'Flanagan, acting president of the Sinn Fein, that time be accorded in which to consult with Eamonn de Valera and Arthur Griffith, founder of the Sinn Féin and now under arrest, respecting the endeavors being made to bring about a truce In Ireland.

The premier in his reply informed Father O'Flanagan that facilities would he afforded him for seeing Arthur Grifflth. Regarding De Valera, the premier wrote: "The ordinary methods of communication with America are fully open to you."

The Chattanooga News, December 15th 1920.PREMIER'S STATEMENT ON IRISH POLICY

Friday the Prime Minister, at the opening of the sitting, made a statement with regard to the situation in Ireland and the policy for dealing with it. While, he said, there had been no negotiations, the Government had been in touch with intermediaries; these, however, could not speak for the section which controlled outrage, and the Government were convinced that that section were not yet ready for peace on the basis of the unbroken unity of the United Kingdom, the only basis on which peace could be concluded.

There were signs in Ireland that the failure of the extremists was having its effect upon the population. He referred to the letter from the Galway Council and to the telegram from Father O'Flanagan, the acting President of Sinn Féin, and read the Government's reply in each case.

Father O'Flanagan, he said, was a distinguished and highly respected priest and a man of great courage, but his action, in putting forward a desire for peace, had immediately been repudiated by the heads of the organization responsible for murder. That organization was not of the opinion of the majority of the people of Ireland at the present moment, and the Government's policy must be based on a recognition of those facts.

They could not recognize Dail Eireann; to do so would be to recognize that the part of the country represented by its members constituted a separate Republic. But the individual members were elected under the constitution of this country, and with the exception of certain individuals who were gravely implicated in serious crime, the Sinn Féin M.P.'s would be given safe conducts and protection to meet for the free discussion of the situation; and in order to avoid any suspicion of breach of faith, the Government would give a list of those members to whom a safe-conduct would not be granted.

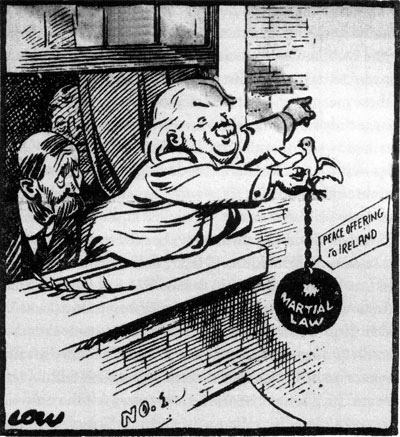

Mr. Lloyd George went on to say that martial law would be proclaimed in the South west of Ireland in order to suppress crime. Under that proclamation all arms and uniforms in the area proclaimed would have to be surrendered within a certain date. Asked whether he would allow time for the House to discuss these proposals, the Premier said he did not think a debate would be helpful, but if a section of the House wished for a discussion, the Government would not refuse facilities.

EFFORTS FOR PEACE: THE SECRET PARLEYS

At conversations which took place between a Government official and a leading Irish business man directly representing the Sinn Féin leaders at a Government office and the correspondent's room at the Tribune's London offices, a bridge was built which had been adopted by the Prime Minister.

"That bridge consists in allowing the Irish members to meet, but not Dail Eireann, which is a Republican Parliament, but which is composed of the Irish members elected to the British House of Commons."

Having got into touch with members of the Sinn Fein executive in October, he met and talked with the Irish business man, who, being taken to a Cabinet Minister, explained that, while a fisherman for salmon, he would not reject trout.

After seeing Mr. A. Griffith and further conversations the following proposal was framed on November 12: "'Suppose Dail Eireann was allowed to meet under guarantees of the safety of the members, would its first act be to call off the murders of police and soldiers, the British on their side ceasing reprisals?' The envoy's answer was 'Yes,' but he agreed to go to Ireland again to get an authoritative answer."

After the Dublin murders on November 21 it was feared that the conversations might be broken off, but the correspondent succeeded in obtaining assurances from Mr. Griffith that he would do all he could to prevent a rupture, and hoped that the Government on their side would prevent reprisals. Then came the arrest of Mr. Griffith, unknown to Downing Street, and the envoy returned to Ireland on December 3 and set to work to put an end to the murder campaign.

This was followed by Father O'Flanagan's peace offer and the resolution of the Galway County Council, which caused the Prime Minister to act on the formula agreed upon, allowing members of Dail Eireann to meet as members of the British Parliament. "Of course," concludes the Chicago Tribune correspondent, "during this time the Prime Minister saw others concerning Ireland, including Mr. George Russell (A.E.) and Archbishop Clune (of Perth, Australia); also he saw the Lab our leaders who had been in Ireland, and I am informed that they all told him that the only men who could 'deliver the goods' were the members of Dail Eireann."

To the letter of the Galway County Council the Government has replied welcoming every indication on the part of representative persons of a desire to co-operate in the work of peace. For the re-establishment of normal conditions, the cessation of murder and crimes of violence was the first necessary preliminary without which no step could be made towards a political settlement.

The Government were prepared to facilitate the meeting together for this purpose of persons duly elected to represent constituencies in Ireland with the exception of those gravely implicated in crimes, for which they must be brought to trial. Meanwhile, effective measures must be taken to ensure the cessation of murder and violence and the surrender of arms. A reply to the same purport was also sent to Father O'Flanagan with the addition that the Government adhered to the conditions laid down by the Prime Minister as those to which any political settlement must conform. Father O'Flanagan's reply to this was published in Tuesday's papers.

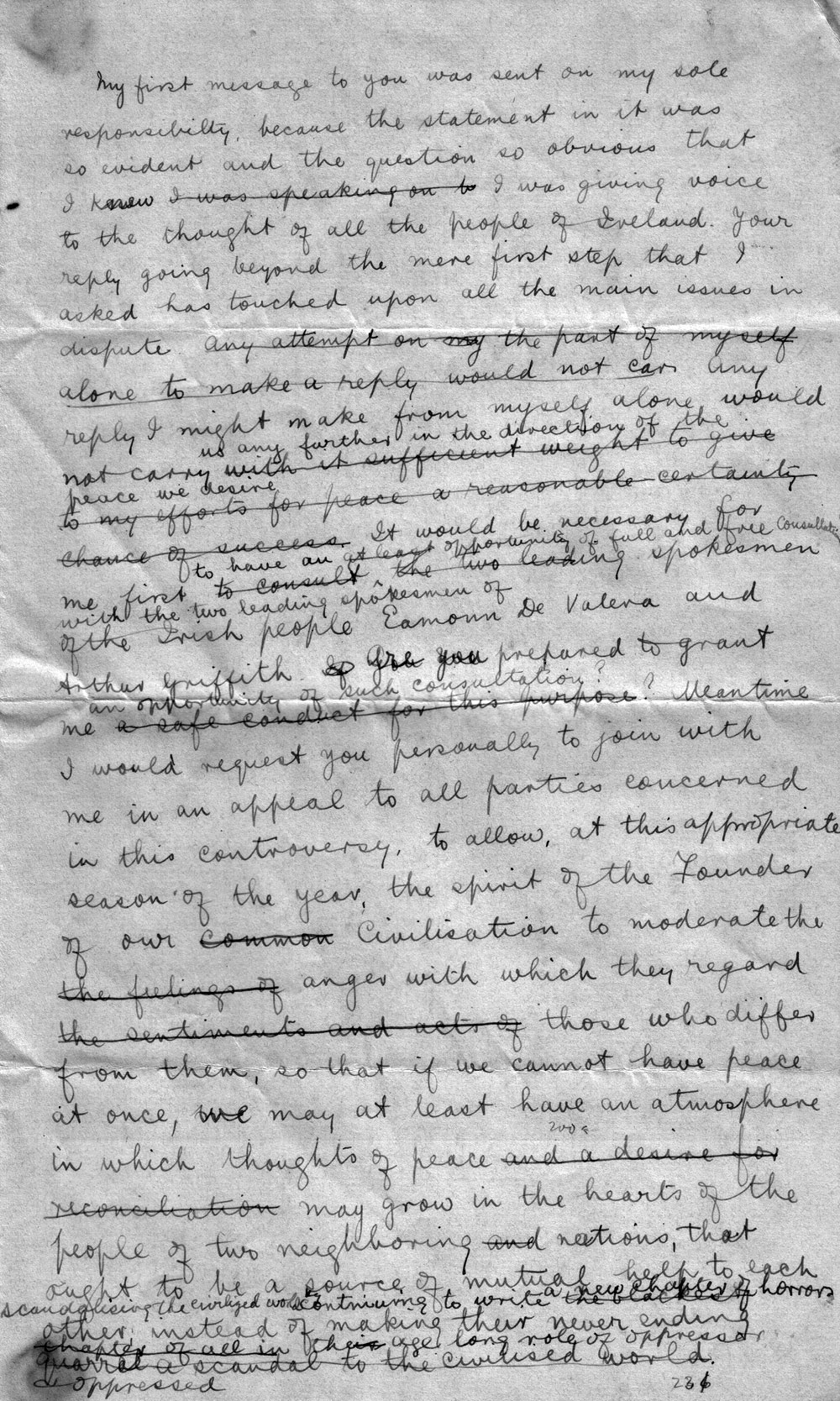

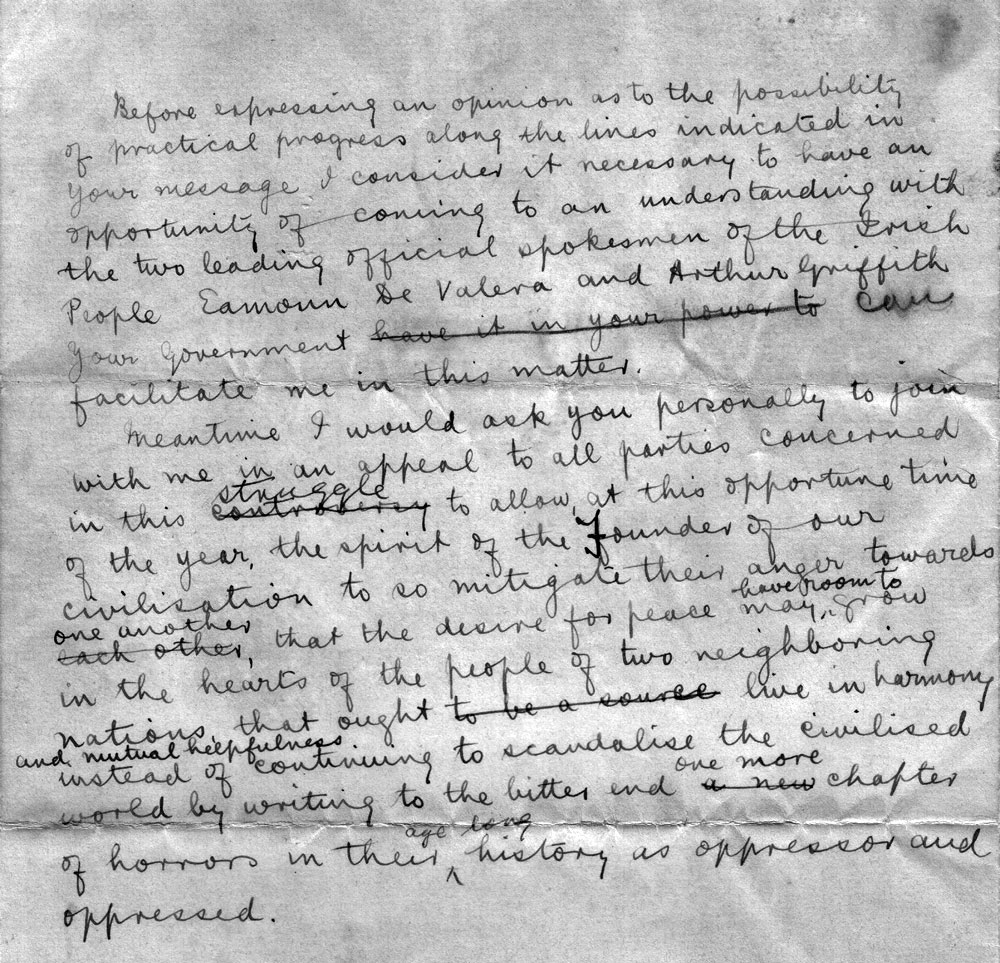

AN EXCHANGE OF LETTERS

He stated that before expressing an opinion as to the possibility of practical progress along the lines thus indicated he must have the opportunity of consulting Mr. de Valera and Mr. Arthur Griffith; and in this matter the Government could help him. Meantime he asked them to join with him in an appeal to all parties concerned in the struggle to allow this opportune time of the year to mitigate their mutual anger so that the desire for peace between the two nations may have room to grow.

In reply to this the Prime Minister sent word that the Irish Government would afford him facilities for seeing Mr. A. Griffith and that the ordinary means of communication were available for consulting Mr. de Valera. He hoped that as a result violence and intimidation would be abandoned and the Irish people would be free to return to those constitutional methods by which alone their rightful aspirations could be attained.

He also hoped that the Christmas season would lessen passion and pave the way for the peaceable discussion with the elected representatives of the Irish people which are essential to remove the age-long misunderstandings which still estrange two peoples whose partnership is essential to one another and to civilization. The Tablet, 18th December 1920

THE PREMIER AND FATHER O'FLANAGAN

Further messages have passed between the Prime Minister and Father O'Flanagan which though for the moment they may scarcely be regarded as helping towards peace have this value, that they make it plain that there can be no settlement of the Irish question on the basis of Sinn Féin's claim for an independent republic. In reply to Mr. Lloyd George's message of peace and good will which we chronicled last week, Father O'Flanagan retorted that the Government had intensified their fiendish attacks on the lives, liberties and property of Irishmen. As the only possible road to reconciliation he made the following suggestion: "If you really wish for peace, allow the constitution adopted by the Irish people at the last General Election to perform its legitimate functions, and acts of violence will soon become as rare in Ireland as they are in any of the most peaceful nations in the world. Then arrange the terms of a treaty by direct negotiations with the official head of the Irish nation, President de Valera."

In the course of his reply to this communication the Prime Minister said that he had hoped that moderation and common sense on both sides might lead to an understanding. It was now implied that the only way to peace was the recognition of an Irish republic and the negotiation of a treaty with one described as its official head. "I have never failed to make it clear that there is no possibility of settlement so long as Sinn Féin demands an Irish republic, and that, though I am willing to explore every avenue towards an honorable and constitutional settlement, there is no road to peace so long as Sinn Féin persists in trying to compel any settlement by the methods of assassination and violence. The only way to peace is that the leaders of Sinn Fein should recognize these fundamental facts."

Father O'Flanagan's reply was to the effect that both agreed on peace and reconciliation in peace as desirable, and that peace could be obtained by the Government ceasing to violate the Constitution by its attack on the liberty of the Irish people. Sinn Féin was a peaceful political organization, and if the attacks on it were stopped, reactions would automatically cease. "Reconciliation can only come when the accredited representatives of both nations meet as equals and draw up an agreement of both peoples."

He had not closed the door, though he might have discovered it closed when he had thought it open. The Tablet, 25th December 1920

O'FLANAGAN AND LLOYD GEORGE CANNOT AGREE

By The Associated Press London, Jan. 10. —

Conferences between Rev. Michael O'Flanagan, acting president of the Sinn Féin, and Premier Lloyd George, with a view to bringing about peace in Ireland, have been broken off and will not be resumed, says the Daily Mail. Before Father O'Flanagan returned to Ireland on Friday night he had a long conversation with the premier and the outcome is said to be described in official quarters as "not as satisfactory as could be hoped." Peace negotiations have not altogether broken down, the newspaper adds, but Father O'Flanagan will not be a party to further exchanges. The Cornell Daily Sun, Volume XLI, Number 79, 11 January 1921

IRISH PEACE

Amid a multitude of rumors as to what is being done in the interests of peace one thing at least is certain, and that is that the conversations between representatives of the Government and of Sinn Féin are not suspended, and that events are moving in the direction of further negotiations. Mr. de Valera is now in Ireland, and though as yet he has made no pronouncement of policy, a forecast of what he may be expected to say has been put forward by the Freeman's Journal. According to this Mr. de Valera maintains "that any peace move must have for its basis the recognition by the English Government that Ireland is an independent nation. When the representatives of the English nation are prepared to meet the representatives of the Irish nation on an equal national footing peace talk will be possible."

Does this mean that whilst Mr. de Valera is ready to negotiate he is holding out in the hope of better terms; that he remains an irreconcilable Republican desirous of stimulating the militant campaign; or that his pacific intentions are being overborne by extremists of his party? The Archbishop of Perth has left this country, but while in Paris gave an interview to the Liberaté in which he asserted his belief in the sincerity of Mr. Lloyd George's desire for peace. But some members of the Cabinet thought that the British people would not be satisfied with a truce negotiated before the Irish laid down their arms - a view to which the Prime Minister seemed ultimately to have rallied.

Father O'Flanagan, the acting President of Sinn Fein in Mr. de Valera's absence, had an interview at his own request with the Prime Minister on Thursday in last week, at which Sir Hamar Greenwood was present. There was a very frank interchange of views, says the Times. Father O'Flanagan explained the aims and aspirations of Sinn Féin, and was answered in unequivocal language by Mr. Lloyd George, who, whilst ready to do all he could for peace, insisted on the three conditions which he had repeatedly set forth, and especially on the refusal of any recognition to an Irish Republic. After the interview Father O'Flanagan returned to Ireland to communicate with his colleagues.

The Tablet, 15th Jan 1921Excerpt from: The Attempt to Make Peace With Ireland

by W. P. Crozier

Even if Sinn Féin had its way and secured independence, its first duty would be to allow Ulster to exercise the right of self-determination, in which case Ulster would certainly demand to return to the British fold. That this right does belong to Ulster is now openly admitted even by some of the Sinn Féin leaders, and the admission is not only just but helps very greatly toward a peaceful settlement. Thus Father O'Flanagan, at one time Vice President of Sinn Féin, has put the case most powerfully for the separate treatment of Ulster:

"If we reject Home Rule rather than agree to the exclusion of the Unionist part of Ulster what case have we to put before the World? We can point out that Ireland is an Island with a definite geographical boundary. That argument might be all right if you were dealing with a number of island nationalities that had these definite geographical boundaries.

"Appealing as we are to Continental nations with shifting boundaries, that argument can have no force whatever. National and geographical boundaries scarcely ever coincide. Geography would make one nation of Spain and Portugal; history has made two of them. Geography did its best to make one nation of Norway and Sweden; history has succeeded in making two of them. Geography has scarcely any thing to say upon the number of nations of the North American Continent; history has done the whole thing. If a man were to try to construct a political map of Europe out of its physical map he would find himself groping in the dark.

"Geography has worked hard to make one nation out of Ireland; history has worked against it. The Island of Ireland and the national unit of Ireland simply do not coincide. In the last analysis the test of nationality is the wish of the people. A man who settles in America becomes an American by transferring his love and allegiance to the United States. The Unionists of Ulster have never transferred their love and allegiance to Ireland. They may be Irelanders, using a geographical term, but they are not Irishmen in the national sense. They love the hills of Antrim in the same way that we love the hills of Roscommon, but the center of their political enthusiasm is London, whereas the center of ours is Dublin. We claim the right to decide what is our nation; we refuse them the same right. We are putting ourselves before the world in the same light as the man in the Gospel who was forgiven ten thousand talents and proceeded to throttle his neighbor for one hundred pence. England has tired of compelling us to love her by force. We are anxious to start where England left off and to compel Antrim and Down to love us by force." Dearbourne Independent, February 7th 1920

Mr. Lloyd George laid great stress on the differences between Ulster and the rest of Ireland. " It would be an outrage on the principle of self-government to place them [Ulster] under the rule of the remainder of the population." He quoted Father O'Flanagan, a leading Sinn Feiner, and also Professor McDonald, of Maynooth, whose book we reviewed recently, as recognizing that the argument for Irish Home Rule involved Home Rule for Ulster. Mr. Lloyd George declared that three-fourths of the Irish wanted " the right to control their own domestic concerns." But Great Britain would not, and could not, give Ireland independence. Military and commercial reasons forbade it. " Any attempt at secession will be fought with the same determination, with the same resource, with the same resolve as the Northern States of America put into the fight against the Southern States."

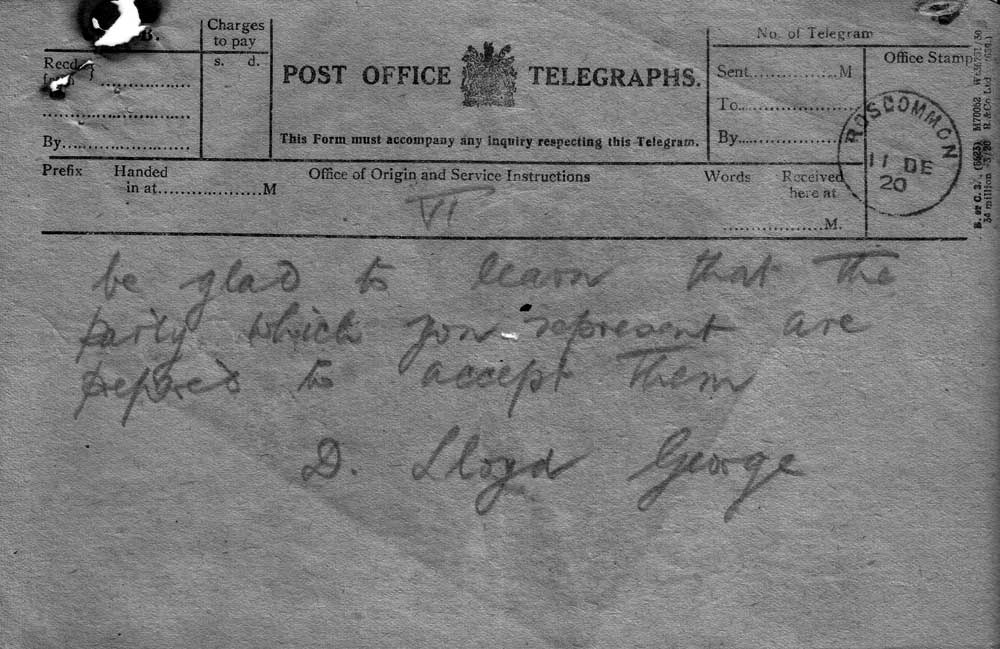

Reply to Fr. Michael O'Flanagan's telegram from Lloyd George, the British Prime Minister.