The Priest as Public Citizen

DENIS CARROLL

They Have Fooled You Again, Michael O’Flanagan (1876-1942) Dublin;

The Columba Press, 1993, £9.99

Reviewed by TERENCE BROWN

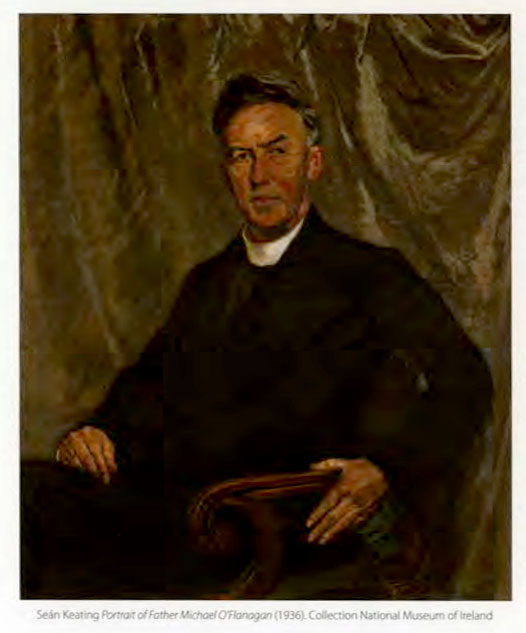

THIS IS a thoughtful, painstaking account of the public life of a very unusual Irish cleric: the republican populist, social critic Father Michael O’Flanagan whose career was dedicated to the cause of Sinn Féin and to the revival of the Irish language in the turbulent period which saw the Great War, the Easter Rising and the Irish Troubles which climaxed in bitter civil conflict.

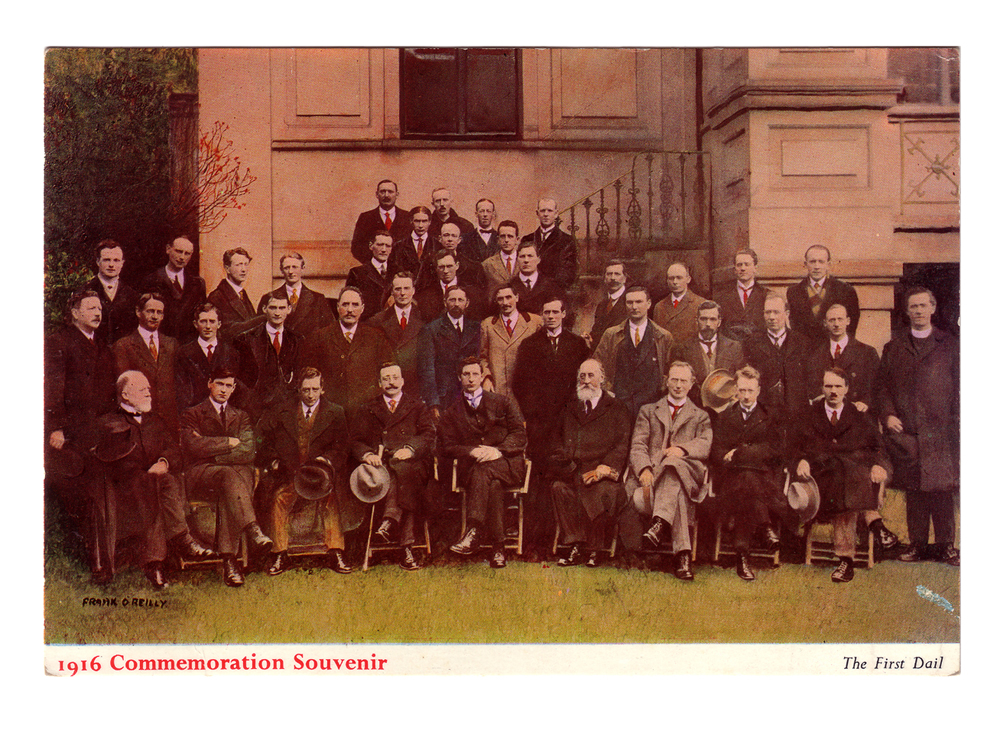

Denis Carroll’s densely-packed narrative (which occasionally suffers from tiresome chronological back-trackings, so complex is the material which must be addressed) takes its subject from a small-farm childhood in County Roscommon, where a mother fluent in the native tongue gave her son an appreciation of the Irish in whose service he was to be so zealous throughout his life, to Maynooth, to a first posting in County Sligo, to work for the Gaelic League, for Sinn Féin whose president he would eventually become in the grim decade of the 1935, and to support for what in Ireland was a most unpopular cause, that of the republican government in Spain, not that Father O’Flanagan had ever governed his life by considerations of what might or might not be thought popular by those in the seats of power in Church or State.

Centenary commemorative stamp issued by an Post in August 2015.

By temperament and inclination a radical populist with anarchist impulses, Father O’Flanagan, in Carroll’s account, lived by the precept enunciated by the Fenian leader John O’Leary (which Yeats so admired): “to pull the bow and tell the truth.” Indeed, the moral force of his thought was as much a matter of its manifest personal disinterestedness as of its occasionally less than assured content.

An advanced nationalist he was nevertheless capable of confronting, even if not in an entirely coherent way, the issue of Northern Unionism, Orthodox republicanism did not wish to hear of a Two Nations Theory. Father O’Flanagan was willing to risk misunderstanding and obliquity when he pondered in print “the island of Ireland and the national unit of Ireland simply do not coincide” and in a sentence that is still tellingly apposite, he questioned: “After three hundred years, England has begun to despair of compelling us to love her by force. Are we so anxious to start where England left off or are we going to compel Antrim and Down to love us by force?”

It was this very independence of mind which perhaps accounted for one of the most curious incidents in Father O’Flanagan’s career, about which Carroll writes with sympathy but some perplexity - that is, his individual attempt during the War of Independence to open negotiations with the British. In these he reached a point, as Carroll admits, when “he represented nobody but himself.”

Carroll exonerates him from charges inevitably laid against him for these strange proceedings by fellow republicans on the grounds of “sincerity.” Naivete might be the more accurate term. For a man who reckoned himself a truth-teller and plain-dealer was not one who could easily cope with the subtleties of a Lloyd George. And it may have been the naivete of a believer in truth that led him to think that in the truth he possessed an invincible weapon, when to deal with a Lloyd George and his government required the cunning of a fox, the devious wiles of a de Valera.

But independence of a very striking kind made of Father O’Flanagan that extraordinary thing, a priest in politics who insisted that in the political sphere he was acting not as churchman but simply as an individual citizen. He supplies accordingly in his writings and in his life the basis for a truly republican understanding of a workable relationship between Church and State.

Not surprisingly, this brought him into frequent, personally bruising conflict with his ecclesiastical superiors, in which he behaved with a great sense of principle and personal probity. And it is as a priest who challenged a hierarchical Church to face what might be the implications of a radical role in a democratic polity that I believe his real importance lies, despite Denis Carroll’s rather strained attempts to make Father O’Flanagan anticipate the insights and procedures of liberation theology and current priestly activism in the Third World.

For all its interest, this biography, it must be said, leaves the reader with little real sense of Michael O’Flanagan the man, however much we learn of Father O’Flanagan the political citizen.

It is only late in the book, for example, that we hear of his sister. We learn tantalizingly too of a Mrs. Larry Nugent who was apparently a “confidante” during the period when he was in contact with the British, but of her we are told nothing substantial.

Nor, despite frequent references to J.J. O’Kelly, the highly influential editor of The Catholic Bulletin, do we get much sense of this man who was one of O’Flanagan’s closest friends, with whom he eventually disagreed on the issue of the Spanish Civil War.

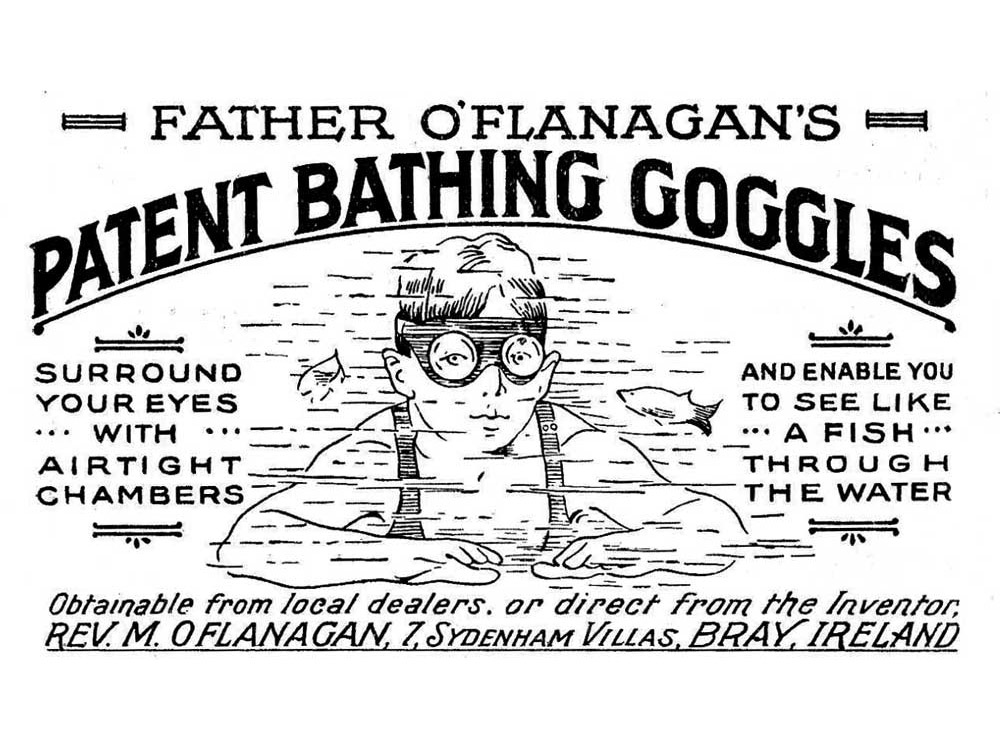

What Carroll does tell us about Father O’Flanagan’s personality, about his scientific projects, his dedication to local history, his practical man’s interest in such things as the national diet and the benefits to be derived from oaten bread, simply whets one’s appetite for more. It makes one wish that the author had given more space to Father O’Flanagan’s milieu, his friends and enemies, to his personality, to motivation and to the quality of his spirituality and theology than to the minutiae of republican politics in the post-Treaty period.

That would have made for a friendly book, more true, one imagines, to a man renowned for his populist, homely oratory and down-to-earth grasp of the concerns of his congregations and audiences.

-Trinity College Dublin.

Source: https://newspapers.bc.edu/?a=d&d=irishliterary19940901-01.2.42&