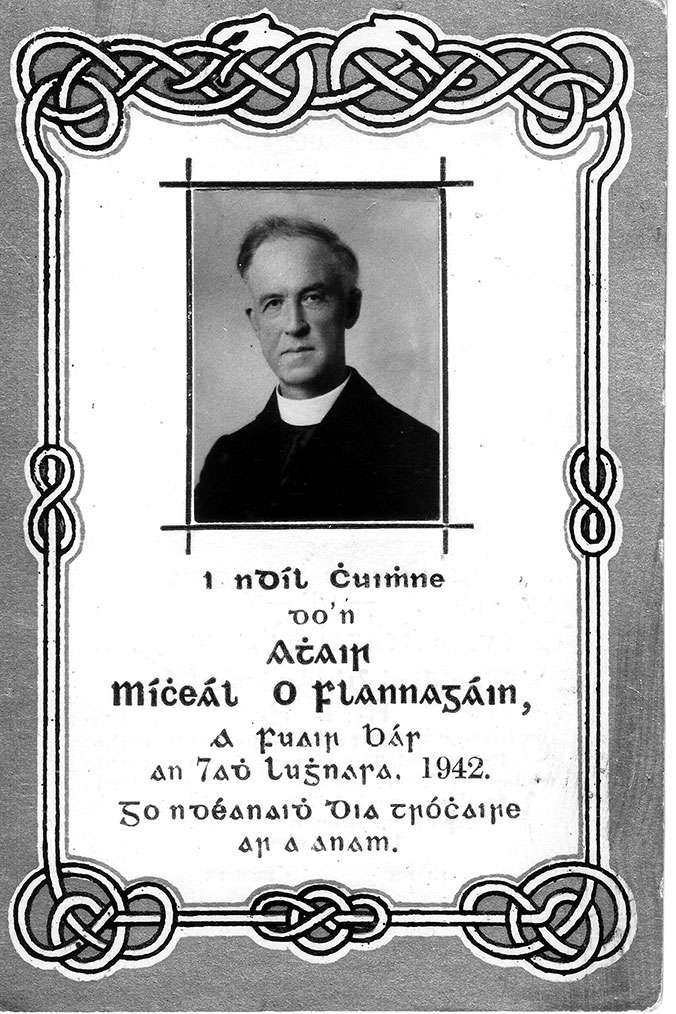

Sceilg's Graveside Oration

August 10th 1942.

I have been asked to say a few words at this graveside on the lifework of Fr. Michael O'Flanagan, a subject so delicate as to be almost sacred, some will think; too serious and too sacred, to my knowledge, for casual comment or loose thinking.

In my present state of health—and of anguish—I comply only because the request has been conveyed to me as a dying wish of the patriot priest whose remains we now lay amid the hosts of martyrs consecrating this historic city of the dead. Concisely, truthfully, and with the deepest reverence for the sacred office to which he was called, what has to be said is this:

For close on forty years I have had the privilege of a growing familiarity with the departed patriot. It happened that his chosen companion at Maynooth College was a relative of mine—a young man of rare charm and devotion, who passed away before ordination—and that early bond helped in the course of the years to cement the attachment between us.

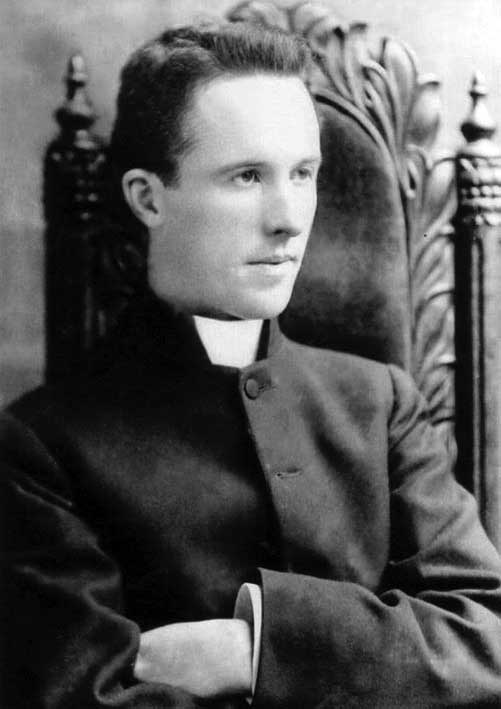

Father Michael was a very young priest indeed when first sent to the United States in the joint interest of a Religious Order and of native Irish industry. His simple manner and his racy eloquence proved from the very outset the passport to the hearts and the minds and the purse-strings of our exiles, and so his mission was a pronounced success.

Soon afterwards he was sent on a second mission in the interest of the national language. On this occasion his innate modesty and bewitching oratory brought him a still greater measure of success accompanied, I regret to say, by the inevitable envy in high places.

On his return home, he combined with his diocesan duties the furtherance of the Gaelic League and all it stood for; the study of genealogy and local history, the awakening of the people's self-respect, the rousing of the spirit of liberty. In the crisis of the World War he went out into the moorlands with his flock, urging them by word and example, to provide the necessary fuel for the critical winter ahead.

And when he later found that their food was being exported to England:—as had happened during the Black Famine,—he advised the rural population to Stick to the Oats! until the phrase became a clarion-call to the nation. These activities earned him the envenomed hostility of England's executive instruments here; but they created the atmosphere which enabled him in time to secure the election to Parliament of Ireland's first Delegate to the Peace Conference, and to inaugurate the Republican movement on its constitutional side.

Subsequently, when many of the national leaders were deported, to facilitate the intended conscription of our young manhood, the direction of the national movement automatically devolved on him, and he led it with such consummate efficiency—particularly during the historic General Election of 1918—that he became the idol of the people.

Incidentally, his national activities unfortunately brought him episcopal censure; but in deference to universal opinion, his facilities were soon restored and the suspension removed. By that time he had won a place almost unique in the national affection; but the public ardor with which he was everywhere greeted did not affect his priestly modesty by a hair's breadth, or lead him for one moment to forget the sacred office for which he had been ordained.

In due time, with his bishop's approval, he was sent on another patriotic mission abroad. In this third triumphal tour of the United States, leading prelates met and entertained him in all the great cities. Later, I joined him there; and ultimately we were asked to go to Australia. When he reported his presence to the Archbishop of Melbourne to get his Grace's endorsement of his celebrate, as was his unfailing custom on reaching a strange diocese, the illustrious prelate laughed almost hilariously on finding that there seemed room nowhere for his own signature, so crowded was the celebrat with the autographs of the prelates of the United States and other places.

For six weeks in Melbourne we were the guests of the leading clergy; and one of the younger priests among them accompanied us as Secretary during our whole Australian campaign. In Sydney, Fr. O'Flanagan was the guest of Archbishop Collins and on Whit Sunday, as guest of honour, preached the sermon at the celebration of the veteran priest's Diamond Jubilee. It is, however, true that both in Sydney and Brisbane we saw manifestations of episcopal prejudice against our mission.

In Brisbane, indeed, the Archbishop in a long letter to the press, resented our attitude towards a former Jewish Under-Secretary to the alien Viceroy in Ireland, whom we found installed as Governor of Queensland. England's world-embracing propaganda distorted that episcopal statement through a hundred channels, concocted numberless slanders of us and, without our knowledge, sent marked copies of the papers which they tarnished to the Irish hierarchy with the object of misrepresenting us. But no one in Australia misunderstood us!

In Sydney, moreover, we were dragged before the courts for alleged sedition, but acquitted, after three hearings, for want of convincing evidence. Then a carefully-chosen Board of Bigots ordered our deportation so that, after many weeks in gaol by Botany Bay, we were brought back by sea to Melbourne.

The Archbishop had the kind thought to send vestments and a chalice into Melbourne Gaol to Fr. O'Flanagan so that he might celebrate Mass during our detention there, with the intimation that he might retain them so as to be able to celebrate Mass on the ship during our long voyage to Europe: these cherished gifts, I believe, remained in his possession till the hour of his death.

Fr. O'Flanagan never wished to involve anybody in the consequences of his own attitude; yet I feel that signal favor by the most distinguished prelate at the Antipodes, long after the close of our active mission there, will be generally regarded as an adequate answer to those who charge that we associated ourselves with Communists in Australia, and attacked the Irish hierarchy.

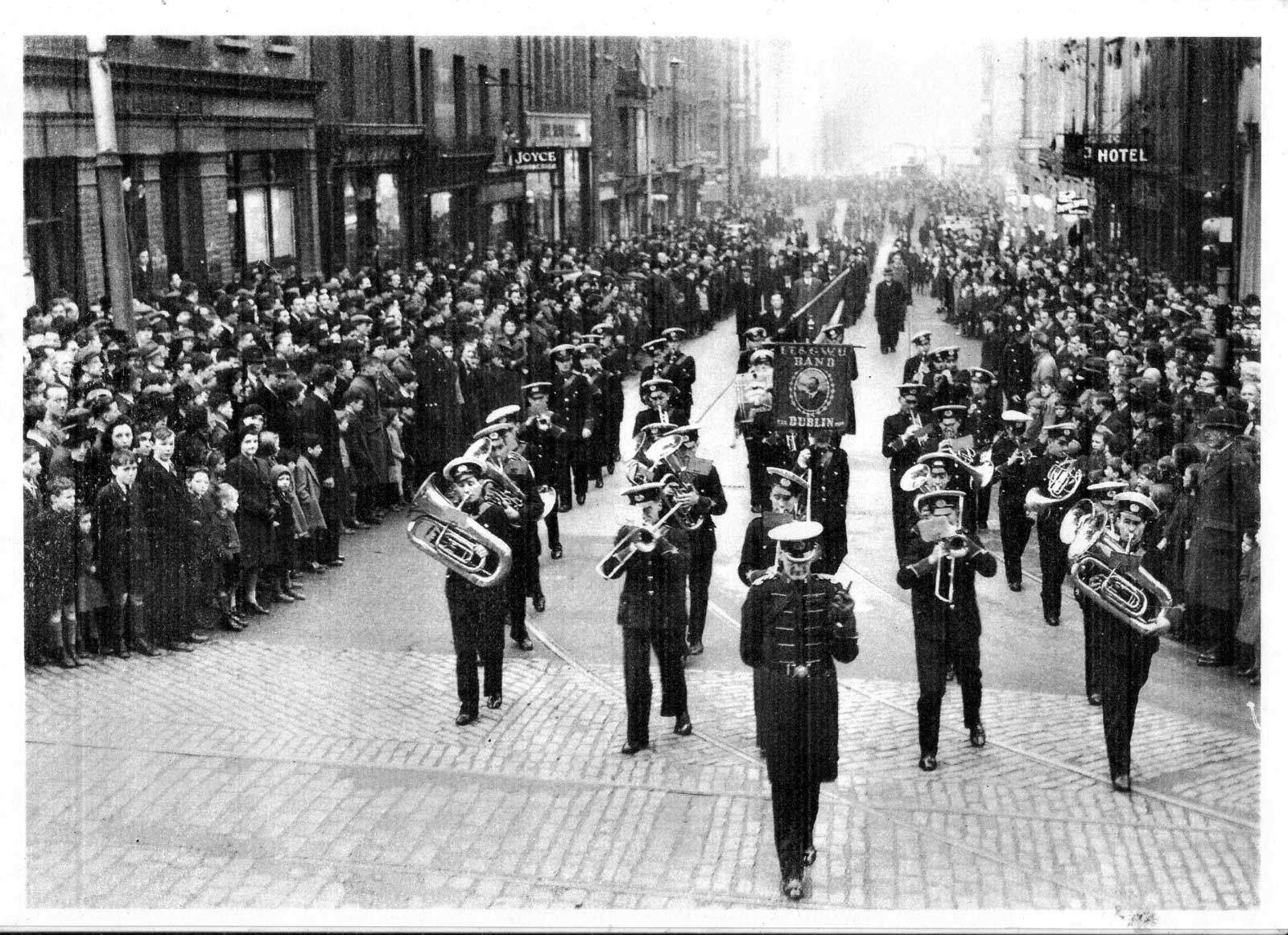

So, too, will the manifestations of respect for the memory of Fr. O'Flanagan which we have witnessed in Dublin for the past three days be regarded as a tribute to his fortitude from the heart of Ireland.

It is true that—as all Irish envoys have spoken in Elks Halls, public Forums and such buildings as were provided by resident sympathizers all over the United States—we spoke in Socialist halls, Communist halls and similar buildings in Australia. But Melbourne is not Moscow, nor is Sydney Sligo, and local priests everywhere presided at our meetings and, in the main, thronged our platforms in spite of all the misrepresentations.

Wherever we went in Australia we found ourselves confronted in the morning papers with flaming extracts from Irish Bishops' Lenten pastorals—taken from their context by England's ubiquitous instruments of propaganda and unscrupulously distorted to discredit our mission. One extract particularly from the diocese of Elphin, was so unbecoming that we could only hope it was recklessly garbled.*

Although the challenge thus hurled at us day after day seemed to leave us no loophole of escape, I am proud to be able to say that Fr. O'Flanagan was never once tempted to retort. I have shared his cabin for three months in the greatest oceans of the world, and shared his ward and served his Mass in Britain's dungeons, at Botany Bay and in Melbourne.

No one living has heard him speak so often in the great cities of America and Australia and elsewhere, and I can solemnly say here at his open grave that I never heard one word fall from those lips that was not worthy of an Irish patriot priest.

Only once during our long and close contact did we find our outlooks differ on anything. In the Indian Ocean one evening the conversation turned on the fate of Charles Stewart Parnell. As the exchanges grew more animated, while we paced the deck, he stopped short and said abruptly: "Why, you remind me of a meeting in Roscommon in my boyhood.

When someone made a hostile reference to Parnell an old man beside me sprang to his feet, and looked around him in disdain. 'Gi' me me hat!' he said, walking out the door." In that breath our discussion ended in a very outburst of laughter, and we went inside for dinner.

That was Fr. O'Flanagan's way: he ever sought and brought about harmony, never consciously deflected from his principles, and had an innate reluctance to re-open avoidable controversy. And although, in the nature of things, he could not always evade the limelight, certain it is that he never once sought it.

In Ceylon, as in Australia and America, he was wont to visit Irish convents; and on reaching Europe his first care was to visit the elevated church of Notre Dame overlooking Marseilles. Later we lingered at Avignon, one-time residence of the Popes, Lyons, Dijon, Paris, Rheims, Genoa, Bobbio, Naples, Palermo, with special regard with to the shrines and associations of Ireland's early saints and missionaries. He was a man of saintly bearing.

One day in Rome, as we left St. Paul's Without the Walls, a lady approached and, taking hold of Fr. O'Flanagan's watch chain, kissed the gold medal suspended from it, a souvenir presented to him by the Pope a decade earlier in recognition of his brilliant courses of Lenten and Advent sermons in the Eternal City in 1912 and 1914.

We returned to Ireland through the United States, Fr. O'Flanagan having been recalled by cable to help in a series of elections then pending here. Some said he made impudent references to the Papacy and other things.

To me it seems the whispers to that effect owed their currency mainly to the envious, and to persons of defective understanding who appear to think that the centre of Christendom—destined to survive by God's promise—is a mere hot-house plant liable to fade away before the first adverse breath, or some tottering institution that can be sustained only by half-truths, suppressions and petty concealments disguised as charity when christian charity is absent.

I have yet to learn that the Holy See resents candid criticism, or has one rule for English ecclesiastics, another for Irish. Most people moderately familiar with Catholic literature are aware that a distinguished English churchman, with episcopal approval, wrote and published the well-known works: the "Papal Monarchy" and the "Papacy and Modern Times."

Who that has read those works will say that a priest like Fr. O'Flanagan, so deeply versed in Irish history, ecclesiastical history, universal history, so familiar personally with the wide world and its ways, should not be free, at the age of fifty, to discuss, as occasion might demand, the attitude of individual Pontiffs towards Ireland's Plan of Campaign, the Williamite Wars, the Confederation of Kilkenny, the earlier mission and struggle of James Fitzmaurice; even the Orange prejudice against the Papacy in our own time, or the triangular relations between the Vatican, Ireland and the British Empire?

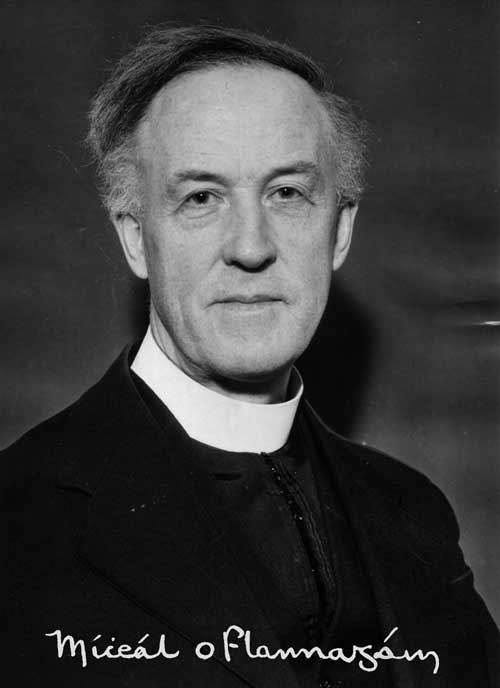

Soon after the close of the miniature General Election of 1925, as it was called, Fr. O'Flanagan intimated to his bishop that his patriotic mission was at an end, and he was ready to resume his diocesan duties. The reply was the withdrawal of his faculties. He was condemned unjustly and unheard; left destitute, or almost so. For a dozen years and more, with the humility which characterized his whole life, he suffered that censure without a murmur.

Not so his friends the world over, who appreciated his character, felt resentful over his position, and took steps to sustain him. I have no wish to dwell on that aspect of the matter beyond saying that, in due time, after investigation of all the circumstances by more exhaled authority, his faculties were restored, Easter 1938. Yet so modestly did he take this vindication that probably not one in ten thousand of the Irish people heard of it in the years that have since elapsed.

The Almighty dowered him also with technical gifts and instincts which would have brought him fame as a scientist. He had the greater blessing that, equally in the face of solitude or of social eclat, he remained as abstemious as a second Father Matthew and, like the Four Masters applied himself with zeal to safeguarding the treasured records of our history, a feature of this work—at which many earnest men had failed—being the voluminous and invaluable Letters of John O'Donovan and placing copies of them in many of the world's leading libraries.

He adhered to his national principles to the last, and never dreamt of exploiting any of the great causes with which he was identified. All through the trials which were his lot he showed the unchanging fortitude and the high courage which emboldened him to confront and confound the Black-and-Tans when they came to take his life in Roscommon in the course of the Terror.

And so, when his end approached, no man ever welcomed any treasure on this earth more eagerly than he welcomed the summons to the judgment-seat. Good-bye Fr. Michael; may God reward your pure, kindly generous christian soul.

Ar deasláim Dé go raib d'anam glan gaedealac, a sagairt is dilse agus is dútractaige d'ar mair nÉireann.

* Under such captions as Brother slays brother! They are of the goats, not of the sheep! The passage most widely exploited was this, from the Most Rev. Dr. Coyne's Pastoral, published in the Sligo Champion, February 17, 1923: "Half-crazed hysterical women, who have not what they want, devote a large portion of their time to the circulation of calumnies and misleading statements about Bishops and priests.

They assist, by carrying dispatches and arms, in the slaughter of some of the best and bravest of Ireland's sons. They glory in the destruction of property and the continued crucifixion of the plain people of the country.

And then (1) with profound piety and brazen effrontery, they kneel in prayer to God and, heedless of Our Lord's warning that 'His pearls were not cast to swine,' they assert the right to the Sacraments and to the other ministrations of the Catholic Church.

(1) British propagandists, by interpolation and paraphrase made the passages close thus: "and, having spent the night on the hillsides with neighbors or sweethearts, approach the altar rails on Sunday morning with brazen effrontery, forgetting that it is not the practice of the Church to cast pearls to swine."

Surely it was not Fr. O'Flanagan that should have been held accountable for the odium arising out of that passage which brought the blush of shame to the cheek of every Irish exile who read it.