What If A Patriot Priest Has Been Traduced?

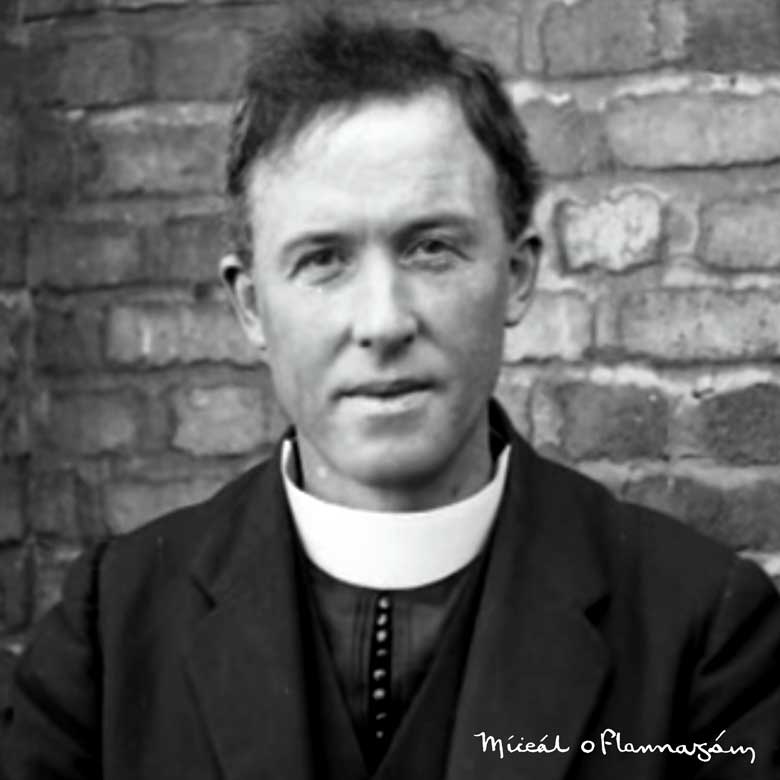

In Defence Of Father O'Flanagan

by Manus O'Riordan.

(This article first appeared in Irish Political Review—Vol 21. No. 7. July 2006).

Diarmuid Ferriter's latest offering—What If? Alternative Views of Twentieth Century Ireland—has met with mixed reviews. But at least it can be said to be a relatively harmless book insofar as it is quite explicitly an exercise in counterfactual historical speculation. It is quite a different matter, however, when facts are stood on their head in what is presented to readers as actual history. It is in his much acclaimed book The Transformation of Ireland 1900-2000 (2004) that Ferriter champions the falsehoods of others, going out of his way to praise Peter Hart for "valiantly" questioning—

"the unchallenged accounts of such events as Tom Barry's Kilmichael ambush… In Hart's view it was a brave ambush that ultimately became a cowardly massacre which involved the deliberate killing of already surrendered soldiers" (p227).

There is no need here to repeat for Irish Political Review readers the total demolition of such Hart falsehoods—so beloved of Ferriter—that has been systematically accomplished by Tom Barry's biographer, Meda Ryan, supported by IPR correspondents themselves, as well as by Indymedia. What I am concerned with in this article is Ferriter's own creation of a completely new falsehood based on the misuse of a Bureau of Military History Witness Statement.

Meda Ryan has, of course, chronicled Tom Barry's own objections to the approach adopted by the BMH in compiling such statements. In my view, Barry went over the top in his complete opposition to the whole exercise.

Without the BMH Seán Moylan might never have been persuaded to produce his own powerful memoir of the War of Independence, since published by the Aubane Historical Society. Nonetheless, no BMH Witness Statement should ever be swallowed unquestioningly without first being compared with alternative accounts of the same events contained in other Witness Statements, as well as with all other available sources.

It is indeed to the credit of the BMH that it placed on file, at his own request, a Witness Statement from Commandant General Tom Barry himself (WS 1743) that consists of little more than a declaration of why he was in fact refusing to submit any such statement! Barry argued:

"There will be no records until a quarter of a century at least has elapsed. Any individual is entitled to make any claim he likes and defame any officers he likes…"

Or defame anybody else for that matter. It is indeed a bitter irony that the first such statement to have its inaccuracies distorted into character assassination by Ferriter is that of the General's own wife (WS 1754). Ferriter writes:

"Mrs. Tom Barry's statement to the BMH recorded that at the time of the Rising in 1916, Fr. O'Flanagan… relented and agreed to travel across town to assist with the injured. Barry was disgusted that when she and O'Flanagan were on their way to the GPO and they passed a drunken tramp who had been shot, 'the priest did not stop for him', but did give absolution to another wounded man.

'You see the difference', she wrote, 'here he knew a man who was respectable'… (and she said to the priest) … 'Isn't it extraordinary you did not kneel beside the other man?'…".

Checking out the Witness Statement itself, we find that coming to terms with her first violent death had been an understandably unnerving experience for Mrs. Barry (neé Leslie Price). On Easter Wednesday she had been with the Army of the Irish Republic in occupation of the Hibernian Bank on O'Connell Street when Captain Thomas Weafer was shot in the stomach and she had been particularly upset on having to leave his body behind when forced to evacuate that building.

She further recounted that next day, Thursday "at 4pm", Tom Clarke said to her in the GPO: "You are to cross O'Connell Street to the (Pro-Cathedral) Presbytery and get a priest". (And this from the one Rising leader who would himself adamantly refuse to have any dealings with a priest at the time of his own execution!). Mrs. Barry further elaborated: "He had the intention of bringing a priest in and keeping him on the premises".

When she was received in the Presbytery, the priest said to her: "You are not going to the Post Office. You are staying here. No one will go into the Post Office. Let these people be burned to death! They are murderers". Mrs. Barry observed: "I knew then, by some other remark Fr. O'Flanagan made, that it was the linking up with the Citizen Army he did not like".

But her response to him was: "If no priest is going to the Post Office, I am going back alone. I feel sure that every man in the Post Office is prepared to die, to meet his God, but it is a great consolation to a dying man to have a priest near him". Mrs. Barry concluded that her defiant statement must have had some effect, as the priest replied: "Very well! I will go".

Mrs. Barry recounted that on their way to the GPO they came across a man in Moore Street,

"who had been shot and was dying on the road, but he had drink taken. The priest did not stop for him. I was horrified. Further down Moore Street … a whitehaired man was shot but not dead. He was lying, bleeding, on the kerb … It was (Irish Volunteer officer) Eimear O'Duffy's father or grandfather.

He was an old man. I remember the priest knelt down and gave him Absolution. You see the difference: here he knew a man who was respectable". When they got to the GPO, "Tom Clarke… said on no account was he (the priest) to be let out of the Post Office".

However, that same Pro-Cathedral priest, Fr.Flanagan himself, has provided us with a somewhat different account:

"My first visit to the GPO was paid on Monday night at nine o'clock in a response to a request from Patrick Pearse… and I was there engaged hearing confessions until half past eleven. During the ensuing two days I attended several men shot in the streets. The military began to close in, on Tuesday evening, and machine-gun and rifle fire made it unsafe to be about".

On Wednesday morning, "immediately after Mass, while on my way to attend two boys shot at 6 Lr. Malboro Street, I had some difficulty persuading a crowd of people that I would be safer alone, and they would be safer at home… Subsequently I got down to Jervis Street (Hospital) and with several other priests had a busy day attending the wounded…"

It was on Thursday morning that Mrs. Tom Barry was to call to the Pro-Cathedral:

"I admitted a young lady who had come from the GPO with an urgent request for a priest to attend a dying Volunteer. It did not seem a very responsible request, considering the way from the Post Office to Jervis Street Hospital was comparatively safe, and that we had stationed two of our priests there specifically to meet such a contingency.

However, I accompanied the messenger back to the GPO by a very circuitous route… We experienced more than one thrill in Malboro Street and while passing by the Parnell Statue. In Moore Street an old friend was shot down just beside me, and I anointed him where he lay.

Some brave boys, procuring a handcart, bore him to Jervis Street Hospital where, after a couple of days, he died…"

"On my arrival at the Volunteers' Headquarters, I looked among the wounded for the patient to whom I had been called, and received a hearty welcome from as gay and debonair an army as ever took up arms. They evidently had felt their organisation incomplete without a Chaplain! and I immediately entered on the duties of my new position, which kept me pretty busy all day.

My services were also in request for the soldier prisoners, one of whom was mentally affected by the unexpected events of the week. We had our first serious casualty about one o'clock when James Connolly was brought in with a nasty bullet or shrapnel wound in the leg. He endured what must have been agony in grim fortitude.

Soon I had another to anoint, and though we had many minor wounds to attend to, these were the only two serious cases …Friday dawned to the increasing rattle of rifles and machine guns. I succeeded in getting… into a house in Middle Abbey Street where I prepared for death a poor bedridden man whose house soon became his funeral pyre…"

Fr. Flanagan's own account has been republished this year in Keith Jeffrey's book The GPO And The Easter Rising. It had first been published in the Catholic Bulletin in August 1918 and was consequently available for inspection by Ferriter, had not this professional historian been so prejudicially dismissive of such a source, even though it emerged as the most authentic "paper of record" of the Rising.

Flanagan's account has the immediacy of having been written only two years after the event, unlike Mrs. Barry's account four decades later, not to mention the fact that her BMH Witness Statement remained under lock and key for a further half a century—and not just the prospect of a quarter of a century that Tom Barry himself had railed against!

I fully accept Mrs. Barry's account that Fr. Flanagan had initially denounced the Rising as the work of "murderers" and would share her suspicion that he had been particularly prejudiced against Connolly's Irish Citizen Army. He may well have been cut from the same cloth and have shared the same social prejudices as the character of the extremely priggish Fr. O'Connor who is portrayed in James Plunkett's novel of the 1913 Lockout, Strumpet City. But Fr. Flanagan had nonetheless been educated by his experiences of Easter Week, and not least by the heroic demeanour of James Connolly.

What Mrs. Barry's statement omitted to reflect on, however, was that on Tom Clarke's instructions she had effectively set out to "kidnap" Flanagan so that he might be compelled to serve as GPO Chaplain, by spinning him a false story in order to exert moral blackmail.

When recalling that the priest had hurried past the dying drunk on Moore Street, Mrs. Barry forgot that he was in fact rushing to the GPO in order to attend to the fictitious "dying Rebel" for whom she had summoned him in the first place. True, he had indeed then stopped to attend to a good friend en route, but this was as much in an actual attempt to save his life.

I must confess that before first reading Jeffrey a few weeks ago I had little concern with that Pro-Cathedral priest's reputation until I then realised that there was a wider issue at stake in respect of the uncritical use of BMH Witness Statements.

It was something quite different that had initially so infuriated me: Ferriter's abuse of an apparent coincidence of names in Mrs. Barry's statement, and his resulting defamation of an entirely different priest.

Ferriter proceeded to put an outrageous spin on the name that Mrs. Tom Barry remembered in error (an error that persistently recurs in her statement) from the moment her narrative reaches the Pro-Cathedral Presbytery and she recounts:

"I was let in by a priest, Father Michael O'Flanagan".

The following is Ferriter's spin (p151):

"The Rising presented the Catholic Church with its own problems, including a fear that it would undermine the bourgeois consensus between constitutional nationalism and the Church's representatives.

Mrs. Tom Barry's statement to the BMH recorded that at the time of the Rising in 1916, Fr. Michael O'Flanagan, later vice-President of Sinn Féin, had remarked of the fighters in the General Post Office: 'let these people burn to death, they are murderers'… But Church disapproval was by no means unanimous".

Apart from the Catholic Bulletin primary source itself, Keith Jeffrey's book is not, however, the only secondary source that makes it crystal clear that the name of the Pro-Cathedral priest in question was actually Fr. JOHN Flanagan. More than four decades ago, in 1964, Max Caulfield's book The Easter Rebellion had already detailed Fr. John's role as "unofficial chaplain to the garrison" in the GPO.

Ferriter's character assassination of Sinn Féin's Father MICHAEL O'Flanagan was as unprofessional as it was unconscionable. In actual fact, among the works cited in Ferriter's own bibliography is Denis Carroll's fine 1993 biography They Have Fooled You Again—Michael O'Flanagan, Priest, Republican, Social Critic.

Even if there had been another Michael O'Flanagan based in Dublin's Pro-Cathedral—which there wasn't—an elementary check would have established beyond doubt that it could not possibly have been the same Fr. Michael O'Flanagan whom Ferriter sets out to revile, since he had remained a curate based in the Roscommon parish of Crossna right throughout 1916.

Moreover, O'Flanagan had never been a "constitutional nationalist"—to quote Ferriter's value-laden term for Home Ruler—but was already a member of Sinn Féin's Executive.

Far from being a priest who could ever have been horrified by the Irish Citizen Army, as Mrs. Tom Barry presumed "her" Fr. Flanagan to have been, the Roscommon priest had already been to the fore in supporting Jim Larkin's Sligo dockworker members when they had gone on strike in 1913.

Indeed, O'Flanagan had been a uniquely perceptive and farsighted Sinn Féin leader, as his biographer Denis Carroll details under the sub-title of "two nations theory"(pages 44 to 50). It was O'Flanagan who had argued over the course of a series of articles between June and October 1916:

"The island of Ireland and the national unit of Ireland simply do not coincide… Geography has worked hard to make one nation out of Ireland, history has worked against it… The Unionists of Ulster have never transferred their love and allegiance to Ireland… We claim the right to decide what is to be our nation. We refuse them the same right…

After 300 years, England has begun to despair of compelling us to love her by force. And so we are anxious to start where England left off and are going to compel Antrim and Down to love us by force… If anyone wishes to know another's nationality, the ultimate test is: Ask him…

The only sense in which I am partitionist is that I claim the right of the people of East Ulster to decide whether they are to throw in their lot with the Irish Nation or not. That there should be any doubt about their doing so is at least as much our fault as it is theirs…

We have to come to an agreement with the Ulster Covenanters, even though it be only an agreement to differ. We have to begin to treat them as fellow men. If we go a little further along the road, we may find that after time they will be willing to treat us as fellow countrymen… The Ulster difficulty is Ireland's opportunity. When we solve the Ulster difficulty we shall realise the dream of past generations of Irishmen…

When we are in a position to assert that such double interference (of Church in State and vice versa) has not merely ceased but that we have provided against all reasonable possibility of its recrudescence, then we shall stand upon that clear and solid ground… for us to educate and win Ulster".

For uttering such heresies O'Flanagan drew the particular ire of the Hibernian House Home Rule leader, John Dillon, who denounced him as a partitionist. And yet in February 1917 it was to be O'Flanagan, in his native Roscommon, who would drive the first post-Rising nail into the coffin of Dillon's own Party by initiating, organising and masterminding the victorious Plunkett by-election campaign.

Southern Unionist alarm was expressed in the Irish Times reports that for twelve days O'Flanagan had been "up and down the constituency, going like a whirlwind and talking in impatient language to people in every village and street, corner and cross-roads", as he proclaimed that it "would be better and easier for young men in Ireland to carry their fathers on their backs to the polls to vote for Plunkett rather than have to serve as conscripts in the trenches in Flanders".

A horrified Irish Times foresaw that, as a consequence of O'Flangan's initiative and leadership, Irish democracy was poised to sweep the polls and Dillon's Parliamentary Party "would be swept out of three quarters of their seats in Ireland by the same forces that carried Count Plunkett to victory in north Roscommon, believed to be so peaceful and so free from Sinn Féin and the rebellion taint" (Carroll, pp 56-58).

Carroll recounts O'Flanagan's no less significant role during the 1918 General Election campaign itself:

"At a rally in Ballaghadereen, the home town of John Dillon, O'Flanagan contrasted the record of the Irish Party with that of 'the men of Easter Week who really saved Ireland'. On the one side were those who strove to enlist the young men of Ireland in the British Army. On the other side were the insurgents of 1916 as well as some old Fenians and 'some mad curates with them'.

While the leaders of 1916 were dead or in prison, their followers were free. While the leader of the Irish Party and his two sons were very much alive 'his followers (were) dead in the Dardanelles or in Flanders…' The protest of 1916 had ensured that many thousands resisted enlistment…

At Gurteen (Sligo)… O'Flanagan rehearsed the supinity of the Irish Party in regard to England's war policy. Although John Dillon, rightly, did not let his sons join the British Army 'it was disgraceful for him to ask other men to send their sons'… It was, he declared, the rising of Easter Week which showed the world that Ireland was not free.

Like nestlings, the Irish Party had kept eyes closed and mouths open to take whatever England gave—the worm of Colonial Home Rule… Police reports of the time state no more than the truth: 'He (O'Flanagan) is undoubtedly the only platform speaker of power in the (Sinn Féin) party… and he remains the first apostle of the anti-British faith and no one has laboured more strenuously or effectively against recruiting'…"(pp91-97).

Small wonder, then, that when Cathal Brugha presided over the inaugural meeting of Dáil Éireann in January 1919 and began by calling upon Father O'Flanagan to open the proceedings, he hailed him as "the staunchest priest who ever lived in Ireland"—a fitting riposte to the character assassination of Ferriter's make-belief "history".

by Manus O'Riordan.

Source: Irish Political Review.

Letter to the Irish Times on this topic, Manus O'Riordan, 17th December 2018.