Carrowmore 3

When the first dates from Burenhult's 1977 to 1979 excavations were published, Carrowmore appeared to be maintaining its record-making reputation. Several of the samples returned unusually early dates, some seemingly indicating activity before the arrival of farming to Ireland. This data was used by the excavation director as evidence that Carrowmore possessed some of the oldest megalithic monuments, not just in Ireland, but anywhere in Europe. Burenhult's quick reporting of the dates meant that the site hit the headlines in a major way, prompting articles in the national and international media.

Carrowmore Re-visited - Robert Hensey and Stefan Bergh, 2013.

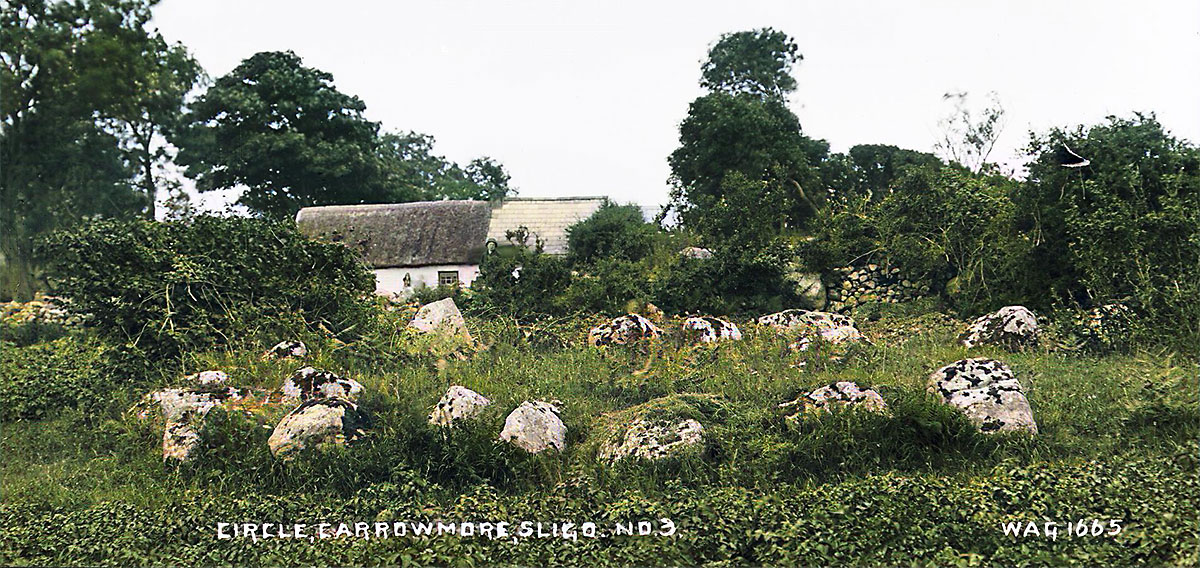

Carrowmore 3, a small and relatively innocent looking monument, turned out to be one of the more contraversial circles at Carrowmore when Swedish archaeologist Göran Burenhult published a series of extremely early dates after his excavations in 1979. This monument is a classic example of a tertre or early open air passage-grave, where the central burial chamber is supported by a platform—the tertre—which is enclosed by a ring of boulders or kerbstones. A symbolic passage, formed from two lines of boulders, connects the stone circle to the chamber. Circle 3 is one of the most complete monuments remaining at Carrowmore, and is located directly across the road from the Visitor Centre.

There are thirty boulders - glacial erratics from the nearby Ox Mountains - arranged in a ring which measures thirteen meters in diameter. Four boulders have vanished since Petrie's visit in 1837, leaving a gap on the north-east side of the circle. There are two smaller inner circles, measuring 9.7 and 7.5 meters in diameter. The monument was dug by Roger Walker, who "found an internment" sometime between 1825 and 1854.

The circle was measured and described by Petrie, a good friend of Walker who was his host during his visit, in August 1837, working on behalf of the Ordnance Survey. The circle was excavated by Wood-Martin around 1880, and his report, taken from Borlase's Dolmens of Ireland, is given below.

The chamber and passage are oriented to the south-east, across Circle 57 a few degrees left of the centre of the complex at Listoghil. Resent research has demonstrated that the passage is aligned to the rising position of the extreme southern lunar standstill, an event which occurs every 18.6 years. The passage, the symbolic link between the land of the living and the world of the dead, is just over two meters long, and is formed from two parallel lines of stones, which like the other Carrowmore passages, was never roofed. The chamber has a flagged floor and is roofed by a disturbed gneiss slab. The chamber is much too small for a living person to fit inside.

Excavations

The Swedish archaeological team excavated Circle 3 for the first time in 1979. The photograph below is a photomontage taken of the monument during the dig. These montages were taken by setting up a tall tripod on the site. A camera was slid up one of the legs and photographs of different stages during the excavation process were assembled into montages. I find them to be very attractive images, but the technique never took off in Ireland.

Two quadrants of the monument were excavated at this time, and two cists discovered outside the central were found to be filled with cremated human remains. Between the excavations undertaken by Wood-Martin and Burenhult, a total of 33.5 kilograms of cremated bone, estimated to represent some 50 neolithic people, was found in this small monument. Many fragments of bone and red deer antler pins were found, usually in a cracked and burned condition, which suggests that they were a primary part of the burial ritual.

A striking feature of the find material from Grave no. 4 is the enormous amount of cremated human bones amounting to over 31 kilos. The central chamber itself produced over 11 kilos of bones. These high quantities may reflect the long time-span during which the monument was used, documented by the radiocarbon dates. The intensive use of Grave no. 3 for burial purposes is also demonstrated by the large number of antler pins found with the cremations, 65 fragments, including 7 pieces with mushroom-shaped heads.

Integrated Excavation Report for Carrowmore Tomb 3,

Göran Burenhult, 1979, 1994.

Stone beads, a piece of flint and chert were also found.

The carbon dates from this dig published by Burenhult were extremely early: 5,400 and 4,600 cal BC respectively from charcoal in foundation sockets in cist c. 4,100 and 4,000 cal BC. Charcoal from stone sockets c. 3,800 cal BC charcoal from stone socket of passage c.3,000 cal BC: charcoal from secondary inner stone circle. Five dates fell between 3,300 and 2,500 cal BC.

Based on the four earliest dates from the two excavation campaigns, Burenhult continued to maintain an argument for a Late Mesolithic-Early Neolithic chronology of megalithic construction at Carrowmore. As new dating evidence from other sites became available, and as refinements were made in scientific dating methods, this interpretation of the Carrowmore chronology was viewed more and more sceptically by scholars. Sheridan, however, while dismissing claims for the earliest of Burenhult's Carrowmore dates, argued that some ofthe dates could be evidence for the arrival of an Early Neolithic wave of farmers from northwest France before 4000 cal. BC.

Carrowmore Re-visited - Robert Hensey and Stefan Bergh, 2013.

A more recent dating programme using red deer antler was undertaken by Bergh and Hensey in 2013, which demonstrated that the oldest use of Carrowmore was around 3,800 BC, which fits within the dates from the causewayed enclosure at Magheraboy. The monuments were still in use around 3,000 BC. The dating samples came from two monuments, Circle 3 and Circle 55.