Burials at Carrowkeel

In general interest the Bronze Age cemetery of Carrowkeel is equalled only by the more famous ones of Brugh-na-Boinne and Lough Crew. None of its sepulacral chambers approaches the regal proportions of New Grange, and the rock-scribings that form so remarkable a feature of both the great Meath monuments are entirely absent at Carrowkeel.

On the other hand, the Carrowkeel group displays a greater variety of design: but the main interest of its exploration lay in the fact that there was no evidence that its cairns had been opened and ransacked long since, as in the other places: most of them appeared to be intact, even when ruined, and they gave an important insight into the burial customs of the Bronze Age people.

Assuming that the apparent absence of any disturbance means that at no time subsequent to the period of interment have these chambers been robbed, their contents seem to explode the popular idea that at least the more elaborate of the Irish cairns contained along with human remains, golden torcs or lunulae, or other contemporary treasure belonging to those who were buried in these imposing mausoleums.

The monuments are grand, and there may have been elaborate funeral rites, but a few trinkets alone seem to have accompanied the sepulture.

R. L. Praeger - The Way That I Went, 1937.

Report on the Human Remains - 1911.

By Professor Alexander Macalister, Cambridge.

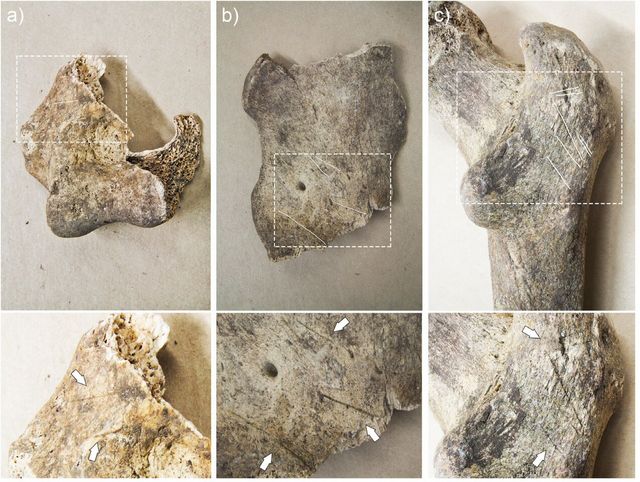

The determination of the characters of the human remains was a matter of very great difficulty. The greater number had been thoroughly burnt and broken, and most of the fragments were, in consequence, quite unrecognizable.

By a careful process of sorting of the fragments and counting the bones that were best preserved, it was possible to arrive at an estimate manner of the minimum number of individuals represented. In this I ascertained that there were bones representing thirty-one skeletons. These, however, constituted only a very small portion, and included only the least perfectly burnt. I think it is a safe conjecture to estimate the number as at least double that limit.

In my first examination I kept the remains from each carn and from each compartment separate, but after carefully reviewing them I found that they were so much alike I consider it unnecessary to describe the several fragments from each place.

In the determinable fragments males preponderated, but there were certainly twelve recognizable females, and probably more. In all carns I found fragments of infantile and foetal bones, but these were few.

There were no men of conspicuously tall stature. The measurements of as were sufficiently complete to give trustworthy results such long bones indicated one man of 5 feet 9 inches, but most of the others ranged from 5 feet 8 inches to 5 feet 5 inches, and the female bones from 5 feet 5 inches to 5 feet. Ten femora and tibiae were sufficiently complete to give definite measurements, and as many more, whose ends were damaged, gave approximate results. The average stature deduced from these was for the males 5 feet 6.5 inches, and for the females about 5 feet 1 inch.

The femora were not unusually stout, and only one showed a slight amount of platymeria. Some, indeed, were proportionally slender. The tibiae were fairly strong, and about one-fourth showed a tendency to platycnemia the others were distinctly euryenemic.

On three tibiae were anterior marginal facets at the lower end, and on four astragali there were the companion facets, and a forward prolongation of the internal malleolar facet. These conditions have been correlated with habitual use of the squatting posture common among Orientals.