The Restoration of Newgrange

Michael J. O'Kelly.

Those of us who knew Newgrange well as a grass-covered mound were startled when we saw it in it reconstructed state with quartz facing dotted with granite boulders giving a ‘currant cake’ effect. The same surprise came to many when they saw the way in which Dr P. R. Giot had reconstructed Barnenez. Yet, both at Newgrange and Barnenez it is clear that these sites, like many another megalithic chamber tomb, were originally revetted with stone walls. Professor O’Kelly has here responded to our invitation to recount how his excavations from 1962 to 1975 enabled him to advise the Commissioners for Public works in Ireland how to restore Newgrange to its appearance 4,500 years ago.

The shape of the Newgrange mound as it has been known to antiquarians and archaeologists during the eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries cannot have been the same as it was when first constructed—this because of the normal processes of weathering and decay and because of interference with it by man and animals.

In 1699 the tomb entrance was accidentally found when some of the edge of the mound was being removed for road metal, but not much damage was then done. Its appearance was more radically changed in the 1870s when the then landowner dug a trench around its base to determine if the kerb, then visible only in the entrance area, was continuous. He constructed a revetment wall to retain the mound material and prevent the kerb from becoming covered again. Much of the material from the trench was thrown to the outside thus creating a bank concentric with the kerb.

This was the origin of the ‘bank and ditch’ which some later observers referred to as an original feature of the monument. Ash and elm trees had been planted on and around the mound in the past and by the 1960s they had grown to full maturity and their penetrating roots had done much damage and further altered the surface appearance. As the mound was not fenced, farm animals (principally cattle and sheep) grazing over it caused various slides and collapses of the mound material which is very largely loose water-rolled stones. This material easily slips, so that by the time our excavations began in 1962, the mound form had become very distorted indeed. Numerous angular fragments of white crystalline quartz were lying about everywhere.

But what can its original finished form have been? Macalister’s threepenny guide book (1939), known to every Newgrange visitor before our excavations began, spoke of ‘a shapely hemispherical mound of stones, the entire surface of which was covered with a layer of broken fragments of quartz’. This was the view then generally accepted and without having given the matter much thought, it was the one fairly firmly fixed in our own minds when we began to excavate the periphery of the structure.

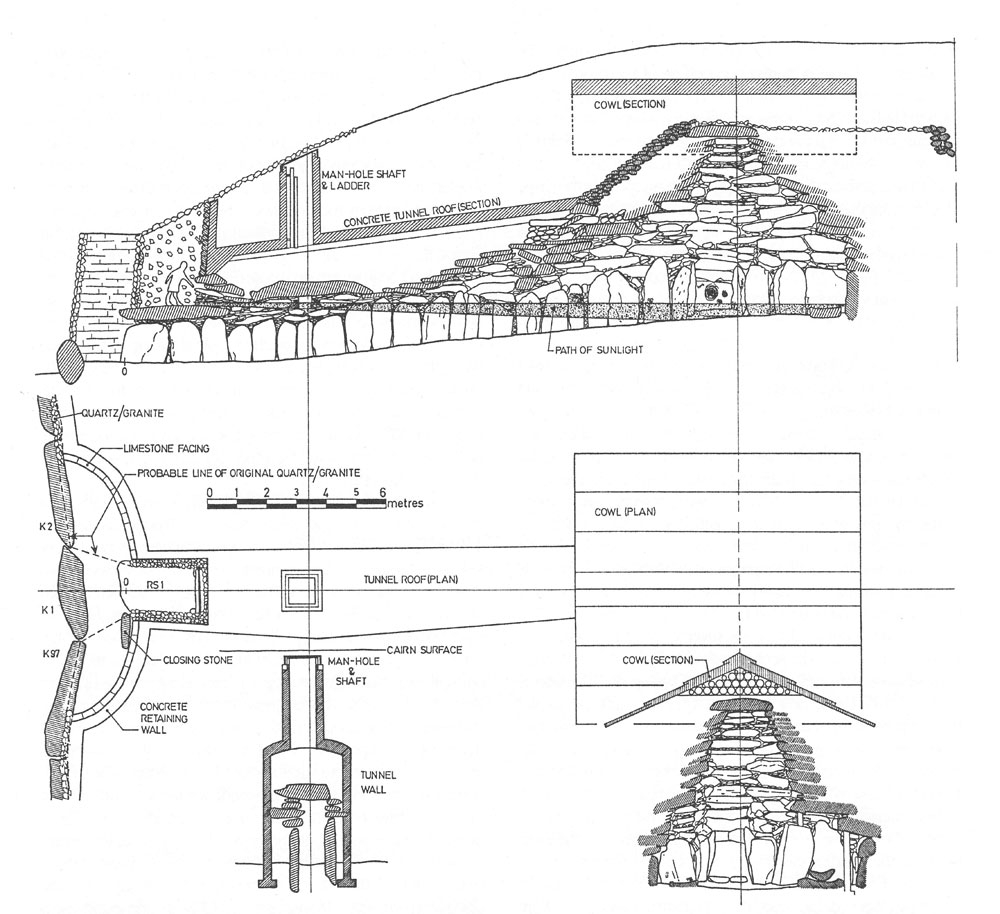

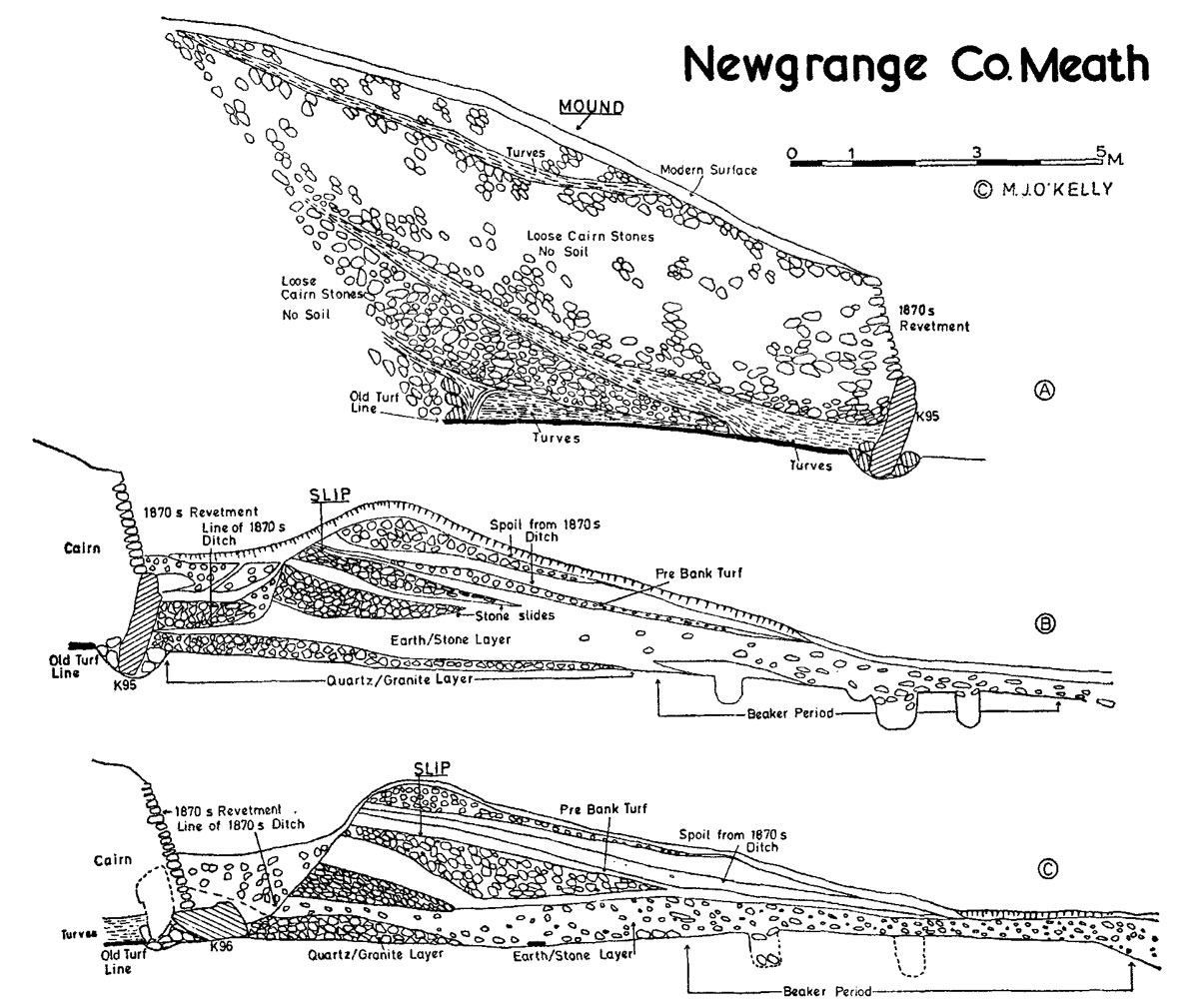

Our first and all succeeding sectional profiles running radially towards the kerb and into the mound itself revealed a curious stratification both outside and inside the kerb. Outside the kerb the topmost stratum of the so-called ‘bank’ was formed of the spoil thrown out when the ‘ditch’ had been dug to reveal the kerb. Below this was a well-marked pre-ditch turf horizon which had formed on the cairn collapse after it had achieved its final angle of repose. Below this turf horizon were two wedge-shaped layers of loose, clean stones with an earthy turf layer between them. The two layers of stones represented sudden slides of the cairn material.

Below the lower layer of loose stones was a layer consisting of cairn stones in a matrix of soil, representing the early decay of the cairn edge which must have taken place slowly enough to enable vegetation to grow through it and on its surface. This vegetation had been inhabited by a vast number of snails whose shells were present in great numbers and represent at least 10 different species. The layer also contained a complex of pottery types including beaker wares, numerous flint artifacts and knapping waste, as well as animal bone food waste. These objects must have been dropped by people squatting on the layer while it was forming. It is C14 dated to 2000 bc (O'Kelly, 1972, 227).

Beneath the snail infested earth/stone layer was a wedge-shaped layer of sharp-edged crystalline quartz fragments intermixed with water or glacially-rolled granite stones resembling a rugby football in shape but smaller in size. This layer averaged about 50 centimetres thick at the kerb face and tailed off outward to nothing at distances varying from 4 meters to 8 meters from the kerb. The layer was thickest and most extensive in the tomb entrance area and tailed off gradually to east and west and was virtually nonexistent by the time K21 on the west was reached and K81 on the east. That is, the quartz/granite layer was present in front of about 20 kerbstones on each side of the Entrance Stone. A cutting on the north side, diametrically opposite the entrance, showed that there had been no quartz/granite here, but in its place a layer of well-selected ordinary stones was revealed.

Some kerbstones had fallen outward completely on their faces (K96 for instance) and in these cases there was no quartz/granite underneath them. This shows that the quartz/granite stones had not been laid as a carpet on the ground in front of the kerb. This being so, the quartz/granite must have fallen from the mound. Since it was a pure layer, it cannot have been laid as a skin on a mound surface that sloped downward to the top of the kerb. If it had slipped from such a position it would have come down mixed with the ordinary cairn material on which it was resting.

Therefore, the quartz/granite must have been built into a wall which stood on the kerb and formed a revetment for the edge of the cairn—a wall which must have collapsed fairly suddenly as a result of outward movement of the kerbstones due to the settlement pressures of the mound material behind them.

The profiles shown in the cuttings made into the edge of the cairn behind the kerb show that the cairn itself has a layered structure, the outer ends of the upper layers of which over-sailed the kerb in such a way that if the cairn material were to remain in place at all, there must have been a revetment wall on the kerb. On the front of the monument for a distance of 20 kerbstones on each side of the tomb entrance, the revetment wall had been built of the glistening white quartz and granite, and for the rest of the perimeter, in ordinary stones selected from the cairn material itself.

When the revetment collapsed it was followed by the loose stones behind it, that is from the edge of the mound and not from its high flat-topped centre. In 1970, when excavation was in progress on the north side of the mound, a line of boulders, the base course of the revetment, was found in situ over kerb-stones 48, 49 and 50.

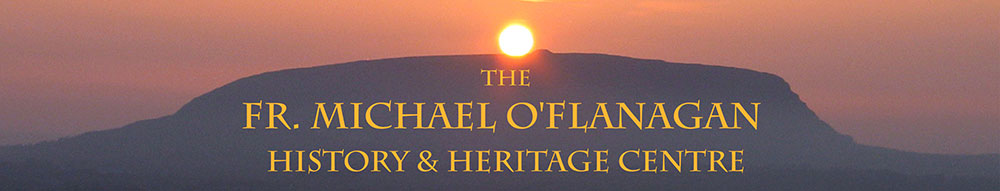

How high was the revetment wall and what form did it take? Research on this matter was done by a consulting engineer whose expertise arises from his studies of mounded loose materials and what happens when they slip and collapse. His research showed that the revetment wall must have been about 3 meters high from its base on the top of the kerb and that it had had an inward batter of 30 centimetres in that height. A full-size experiment was made to test this. A 2 meter-wide trench set radially to the kerb in front of stones 81/82 was carefully excavated and recorded and the quartz/granite at the bottom was used to build a 2 meter-long revetment on the kerb.

This came up to a height of 2 meters using all the larger pieces of quartz and the granite boulders. But there was a residue of quartz fragments too small to use in the building—the quartz that had shattered in the original collapse of the wall. Furthermore, when the trench was dug in the past to reveal the kerb stones, some of the original layer of quartz/granite had been dug out from the top of the thickest part of the deposit just in front of the kerb and had been scattered with the spoil, so that we did not have for our re-building all of the original material. It was not until two excavation seasons later that it became clear to us that we had cut our section at a point where the quartz/granite was petering out altogether, so that there had never been as much of the material here as there had been farther westward towards the entrance.

These various reasons explain the difference in height between our wall and the 3 meter-high wall as calculated by our engineer. As we built the experimental wall we filled in behind it with cairn stones to simulate the unconsolidated cairn edge as it must have been when first built, We then caused the experimental wall to collapse. We re-excavated the collapse and found that its stratification compared almost exactly with that of the original collapse-quartz/granite only on the bottom followed by layers of cairn stones.

Subsequent research (O’Kelly, C. 1978) has shown that other Irish passage-graves have had revetment walls on their kerbs. Conwell, excavating Cairn T in the Loughcrew cemetery reported (1873, 30) that inside the kerb and ‘apparently going all round the base of the cairn was piled up a layer, rising from 3 to 4 feet in height and about 2 feet in thickness, of broken lumps of sparkling native Irish quartz’. This quartz is now scattered on the ground outside the kerb of that monument. Macalister (et al., 1912) recorded a built wall on the edge of Cairn B at Carrowkeel, Co. Sligo, and some of this can be seen in position today.

When the Baltinglass, Co. Wicklow, passage-grave was being investigated over 30 years ago, the excavator (Walshe, 1941,223) found that the inner kerb ‘…..supported a definite wall-face. This extended for about 25 feet in length and was from 4 to 5 feet in height. The wall facing was regularly aligned, receding as it ascended. Enough of it remained to provide evidence of a definite structural scheme, a retaining wall intended to give greater stability to what is believed to have been the primary cairn.’

All of these mounds are of loose stones comparable to Newgrange and a stone-built revetment was a necessity. In cases where the mounds were composed of turves or soil or a mixture of turves, soil and a small amount of stones (Knowth, Co. Meath, for instance) a revetment wall of turves was probably used and in such mounds (much more stable than those of stones) would have been quite effective. The builders of Newgrange, in giving a drum-like shape to the lower part of the cairn, were following a more widespread practice than was realized at the time our excavation began there.

Revetment walls have been found in the cairns of the tombs at Los Millares in the south of Spain and in several passage-graves in Brittany, the most spectacular example in the latter country being the 11 chambered passage-grave at Barnenez, where the revetment walls were found still standing 5 meters high in places and were originally higher—they rise from the ground level as there is no kerb. There the revetment walls turn in at sharp angles to the mouths of the passages as we believe was the case at Newgrange. The Barnenez walls were found to have a batter very similar to that which was calculated for Newgrange.