Art at Dowth

The Dowth legend has the Druid Bresal attempting to build a tower that would reach to heaven. This part is clearly based on a biblical motif, however the incidents which follow seem to relate to the Newgrange legend and reflect native Irish sources.

For a single day, Bresal has contracted the men of Erin to work on the building. His sister works a druidic spell so that the sun might not set until the mound is built. Bresal commits incest with her, interrupting the magic and causing the sun to set. ‘Night came upon them then’, and Bresal’s sister declares, ‘Dubad [or darkness] shall be the name of that place forever.’

And so it is today, but stranger still, one of the two chambers inside Dowth is illuminated by the setting sun at winter solstice marking the longest night of the year. This association of light and darkness with the actual structure of the mound is still reflected in the place-name.

The Stars and the Stones, Martin Brennan, 1983.

The artwork found at Dowth is very mysterious. Most of what we know about the art comes from the survey conducted by Michael and Claire O'Kelly, published in 1983, when they recorded all the engravings they could find on some thirty-eight surfaces. The O'Kellys were very familiar with Dowth, and they used the Netterville Institute as a base during their excavations at Newgrange. Claire O'Kelly undertook her work on the Newgrange art, which was based on full-size rubbings of the artwork, which needed lots of space.

Martin Brennan and Jack Roberts also used the Netterville building as a base, and while staying there he discovered that the chamber of Dowth south is illuminated by the light at the winter solstice sunsets.

Dowth is the least known of the three great mounds in the Boyne Valley, and it's artwork is not well known as a result. Many of the engraved kerbstones are still buried under cairn slip around the edges of the mound. The engravings at Dowth tend to be more primitive than those at Newgrange and Knowth and would seem that Dowth is the oldest of the three monuments.

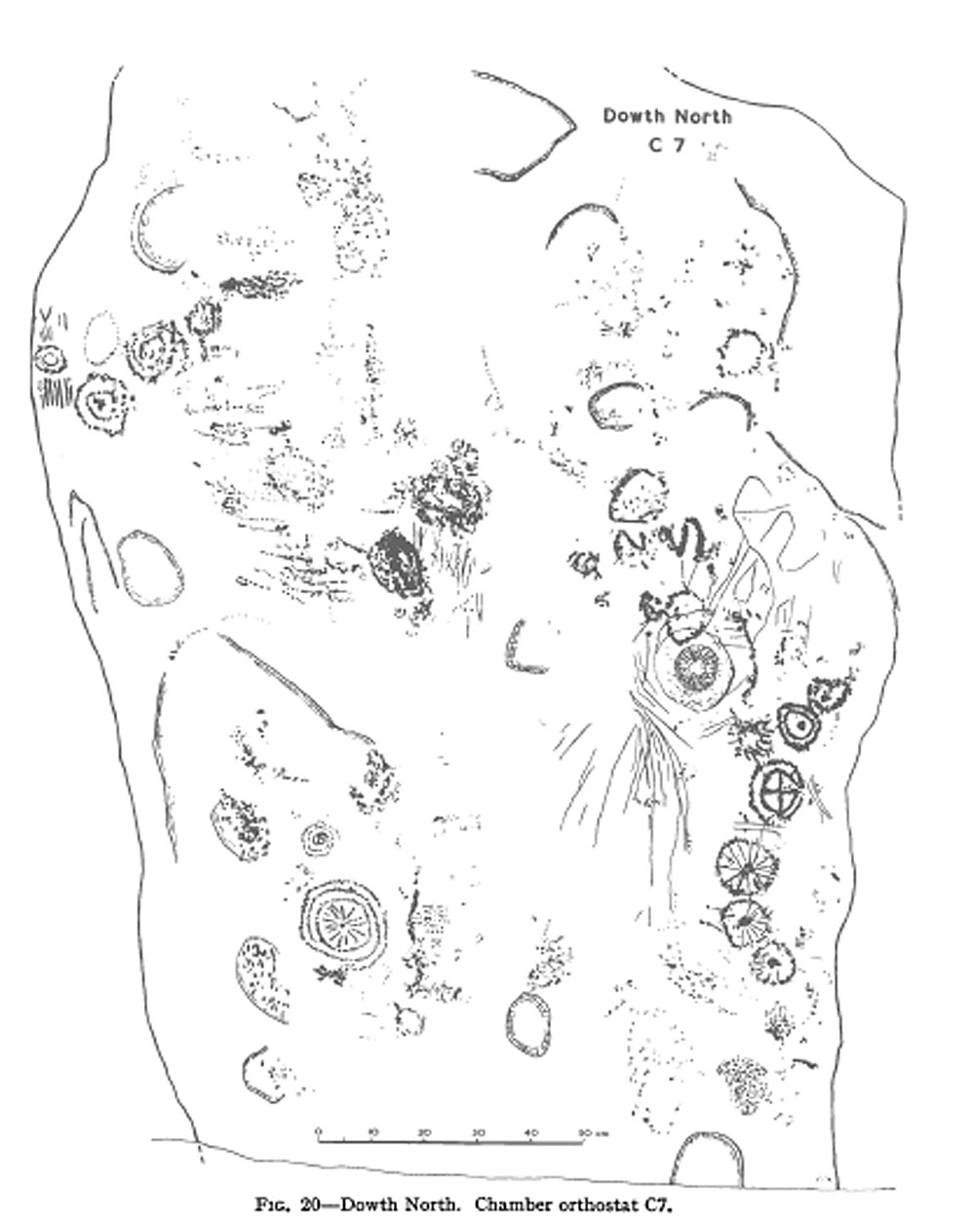

Many of the designs found at Dowth resemble the engraved art from Loughcrew, a site which would appear to be older than the Boyne Valley passage-graves. Of the thirty-eight stones at Dowth which are known to bear neolithic art, fifteen of the kerbstones have decorations, eleven of the stones are in Dowth North and the remaining twelve stones in Dowth South.

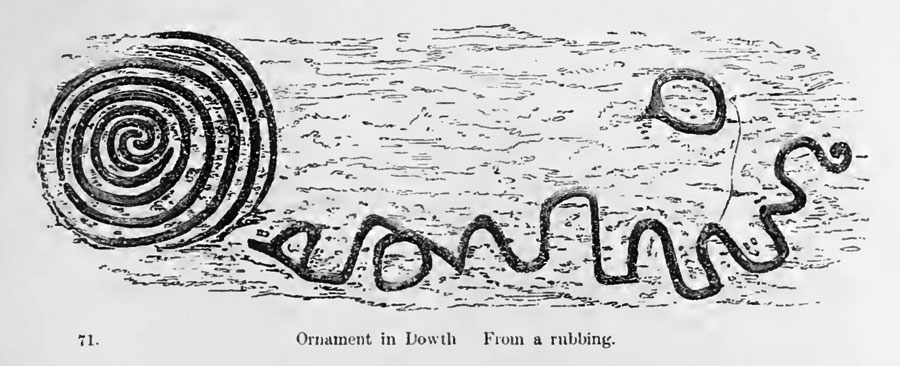

The engravings at Dowth tend to be circular for the most part, sometimes with scratched crosses, along with a few spirals. Wavy, undulating 'squiggles', like serpents without heads, may well be attempts to illustrate the moon's part through the sky. The art at Dowth has a less formal quality than the main stones at Newgrange and Knowth.

The Stone of the Seven Suns

The interior of Dowth is locked and special permission is needed to view the art. The most impressive engravings which can be seen on the outside of the mound today are found on the kerbstone named the Stone of the Seven Suns. This stone has engravings on the front and back surfaces.

The Stone of the Seven Suns is positioned directly opposite the entrance to Dowth North, and, like the Entrance stone and Kerbstone 52 at Newgrange, divides the mound into two parts or halves. These kerbstones were probably used in the setting out and the aligning of the monument. The kerbstone has a line of seven solar emblems, and the name was given by Martin Brennan who became fascinated by the stone when he stayed in the nearby Netterville Institute while writing his book, The Boyne Valley Vision.

The Stone of the Seven Suns at Dowth, Boyne Valley, Ireland. Recorded by Anthony Murphy of Mythical Ireland in 2009.

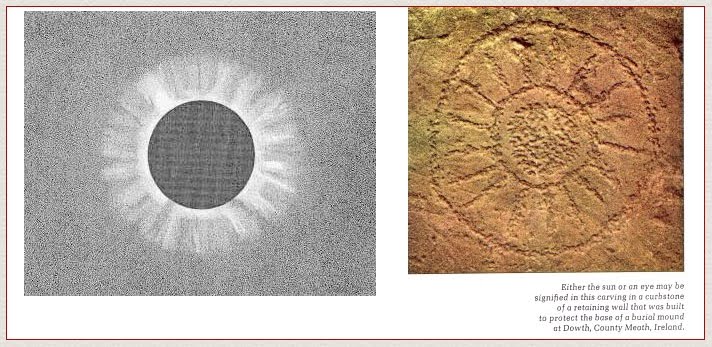

There are five sun wheels laid out horizontaly across the stone, one placed below the others; there are two more rayed circles, and two un-rayed circles. There is also what Martin Brennan described as a calibration offset, a unit of measurement on the top left of the stone. Researcher Robin Edgar has convincingly suggested that these carvings represent total solar eclipses:

The prehistoric Dowth petroglyphs are more than favourably comparable to nineteenth century drawings of total solar eclipses. The inner circle of each rayed-sun has been deliberately pitted to darken it, just as the moon is darkened when it is directly interposed between the Earth and the sun during a total solar eclipse. It is, in my opinion, well within possibility, even probable, that the heavily pitted surface of the inner circle of the Dowth petroglyphs was also intended to represent the cratered surface of the moon.

If this hypothesis is true, it would evidently indicate that the prehistoric artists who carved the Dowth petroglyphs completely understood that total solar eclipses were caused by the glorious conjunction of the Earth's only moon with the sun. An unpitted, or 'clear', ring surrounds the pitted inner circle and it is of a thickness that is similar to that of the bright ring of the sun's crimson chromosphere, or inner corona, which completely encircles the lunar disc at totality. Several straight lines radiate outwards from this inner ring to an outer circle that delineates the outer limits of this 'radiating sun' aka 'radiant divine eye' aka 'compound eye/sun symbol.'

Eclipsology, Robin Edgar, 2009.

Martin Brennan speculated that the engravings on the Stone of the Seven Suns were an attempt to generate a lunar - solar calendar:

K61 and K52 are the only known major compositions on the kerbstones of Dowth. They face eastwards, approximately opposite the entrances of the passages on the western (far) side of the mound. The vertical line on K50 may have had a similar function to that on K52 at Newgrange. Sunwheels on K51 recall those at Cairn T and reveal a similar concern with calendrical fittings of luni-solar cycles. With 6 rayed circles there is also a rayed dot which appears to be a sunset.

The luni-solar symbol on the left suggests that the stone represents a month count, because 12 radials extend from the circle. The next two discs with 14 and 17 radials give a total count of 31, reinforcing the idea of the month count. The count continues to 99 months, which brings the lunar cycle and the solar cycle into extremely close correlation in a calibration of 8 years (363 days x 8 = 2920 days, 99 months x 29.5 days = 2920.5 days).

The 8-year cycle is a very important development in calendar making. Known as the ‘Octaeteris' it was the earliest cycle developed by the Greeks. It neatly contains 5 Venus years (5 x 584 = 2920) and this gave the cycle symbolic as well as calendrical significance in many ancient astronomical systems. The prominent displays of the number 8 may reflect the special significance given to it as representing divisions of the day and year and a cycle of 8 years into which 99 months and 5 complete revolutions of Venus neatly fit.

On K52 the 8 circles and ovals very likely represent the 8 years which are reduced to terms of months on K51. Radials such as those on the stone at Le Petit Mont could represent luni-solar cycles of 18 or 19 years. In megalithic art significant numbers expressed in appropriate symbols seem to recur in prominent positions in astronomical settings,forming a system which is remarkably consistent and unlikely to occur by chance.

The Stars and the Stones, Martin Brennan, 1983.