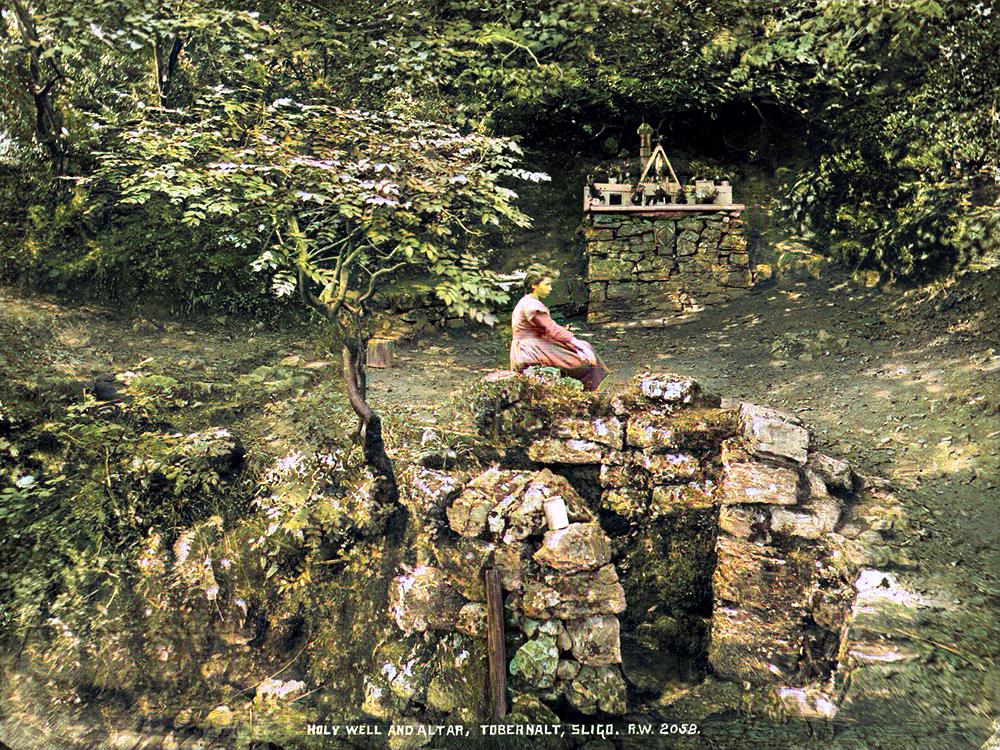

Tobernalt - Sligo's Holy Well

Located in a beautiful and tranquil spot at the south foot of Carns Hill, Tobernalt is an ancient well, and was in use long before the first Christian bell was sounded in Ireland.

At the proper season can still be seen devotees making their tour round the well of Tubbernalt, on the shore of Lough Gill, not far from the town of Sligo. The spring is encircled by a wall of rude masonry, access to it being given by a few uneven steps, and below this spring there is another. Against the overhanging alt or cliff is built an altar, and on Garland Sunday it is gaily decorated with flowers. On either side may then be seen two small framed glasses. Can this be a remnant of the Pagan rite probably alluded to by the Apostle when he says'now we see through a glass darkly'?

Fragments of cakes, pins, and nails may be seen in the well at certain periods, and the locality is at all times festooned with many coloured rags, red, blue, green, white, black, tied up to denote a finale to the rounds and prayers.

Pagan Ireland — W. G. Wood-Martin, 1895.

Tobernalt rises from under the cliff at Carns Hill—and so the site gets its name—Tober an Alt means the Well of the Cliff. The site is located in a grove of trees not far from the western shore of Lough Gill, the enchanted lake with its legendary submerged city.

The Millpond, a tune that is known as the Lough Gill jig around the Sligo area.

The site was used for secret masses during the Penal times between 1690 and 1828, when it was illegeal to practice the Catholic religion openly and there was a bounty on the head of priests.

It is not well known when pilgrimages to wells began. No doubt the springs from which Saint Patrick and the primitive saints took the water with which they baptized their converts were held in veneration from the beginning, as memorials of the national apostle and his associates; but though individuals or small numbers may, on this account, have visited them in pre-Reformation times, it is likely that it was only under the pressure of the persecution and Penal Laws which followed the Reformation, the popular frequentation set in.

When Catholics had no houses of worship they assembled round those venerated wells for the performance of the ordinances of religion; and the small altar would go to show that they not only went through their private devotions in those places, but that they also assisted at Mass there. At first everything passed off decorously and edifyingly, but in the course of time abuses sprang up of so serious a character, that both the ministers of religion and the authorities of the state felt called on alike to stop them.

The first Act to Prevent the further growth of Popery enacted that all "resortings of pilgrims to pretended sanctuaries, Patrick's Well, &c., should be deemed riots and unlawful assemblies;" while ecclesiastical synods condemned some of those "patrons" as "scenes of drunkenness and quarrelling, and of other most abominable vices, by which Religion herself is brought into disrepute, nay, mocked, and ridiculed; intemperance and immorality are encouraged; the tranquillity of the country is disturbed, and the seeds of perpetual animosities and dissensions are sown."

History of Sligo: Town and County - T O'Rorke.

The well rises from a powerful and fast-flowing spring, and it's water is said to have healing properties with cures for both eyesight and madness. The origins of the 'madness' cure may has something to do with Maeve the Goddess of Knocknarea, whose name means 'The Intoxicating One', or possibly the legends of Sweeney the Mad King who is associated with the Cailleach at Sliabh Dá Eán to the south.

Tobernalt is an excellent example of a site that has been continuously used since most ancient times. Neolithic farmers from Brittany had settled in Sligo by about 4,000 BC and constructed many monuments throughout the region. The earliest dated monument is the causewayed enclosure at Magheraboy which is dated to around 4,150 BC, while the two massive cairns on Carns Hill are at least 5,200 years old.

Neolithic Echoes

There are many stories and legends associating Carns Hill and Lough Gill with landscape-goddesses, fairy princesses, and female energies. Indeed, the lake is named after a local princess named Gile, meaning "Brightness". When Gile dies of a broken heart, her nurse, weeping uncontrollably, forms the well and lake with her tears.

Once there was a man building a beautiful boat and when he had it finished he decided to call it "The Lady of the Lake".

One day he went up the lake in it and when he was half way up a mermaid appeared to him and she said "Go back and change the of that boat there is only one Lady of the Lake and that is all that there will be".

So the man went home and changed the name. If he had not obeyed the mermaid he probably would have been drowned.

These stories are all surely pointing back in time, through a haze of Victorian meoldrama, to the neolithic goddess known in this area as the Cailleach named Garavogue. The Garavogue is the chief diety of the neolithic farmers, and she is credited with building many of the great monuments in the area, such as the "Hag's Graves" in Carrowmore, Queen Maeve's cairn, and the monuments on the Ballygawley Mountains, where she has her residence. In the local folklore the Garavogue leaps from summit to summit carrying stones in her white apron.

The Cailleach is the midwife and mother goddess of the neolithic: she attends births and she appears to people close to death. Throughout neolithic Europe stories with the same theme recurr continually at neolithic sites, passage-graves and caves: they are always the home of a powerful fairy woman.

Mouras appear on the interfaces of this world and the otherworld and guard over riches and death and the morals of local people. The toponymes tell us that people were aware of the use of dolmens and caves as burial sites, and the same conclusion can be drawn from the fact that the mouras, who are guarding the borders between the worlds of the living and the dead, were situated especially into the dolmens and caves which had been used as graves. The most important task of mouras and the core of the legends telling about them, seems to be to escort the borning and dying human souls from one world to another, and to gift fertility and health for humans and animals – in other words – birth, life, death and the connection to earth.

Casas das Mouras Encantadas –

A Study of dolmens in Portuguese archaeology and folklore.

Henna-Riikka Lindström.

The Fairy Queen of Lough Gill.

I saw Lough Gill on a summer day

Oh, how serenely fair!

When flash'd on her brow the noontide ray,

And Heaven was reflected there.

How clear that silver mirror shone,

While many a gliding bark thereon

Spread wide at morn her snowy sail,

Or wooed at eve the freshening gale,

Where many "an isle of beauty" lay

Yclad in verdant full array;

And o'er those waves from time unknown

Th' enchantress fair

Whose name they bear

Hath reign'd on her crystal throne;

There her fleet chariot-wheels of old

Over the glassy waters rolled,

And legends say the royal maid

In robe of purest white array'd,

And crowned with diadem of gold,

Still reins abreast three coal-black

Still on her car of triumph speeds,

In royal pride and radiant sheen

Around her native valleys green,

And skims o'er the blue tide's surface cold.Oh, Lady born of fairy land,

Brighter than earth's bright daughters,

For evermore with magic wand

Rule o'er thy realm of waters !

The lake with islets gemmed,

and o'er The wooded banks, the leafy shore

Fit empire for a Fairy Queen.

Did ever morning's dewy eye,

Or the midnight moon from her throne on high,

Look down on so fair a scene?

And if there be a spell or charm

To shed thereon and shield from harm,

O'er yonder lake's unruffled crest,

Nor cloud nor shadow may we trace;

Still peace within her tranquil breast,

Still heaven reflected on her face.

The spring flows into Lough Gill nearby, and the neoltihic people would have revered this site, springs having been held as sacred since earliest times.