Cloghanmore court cairn

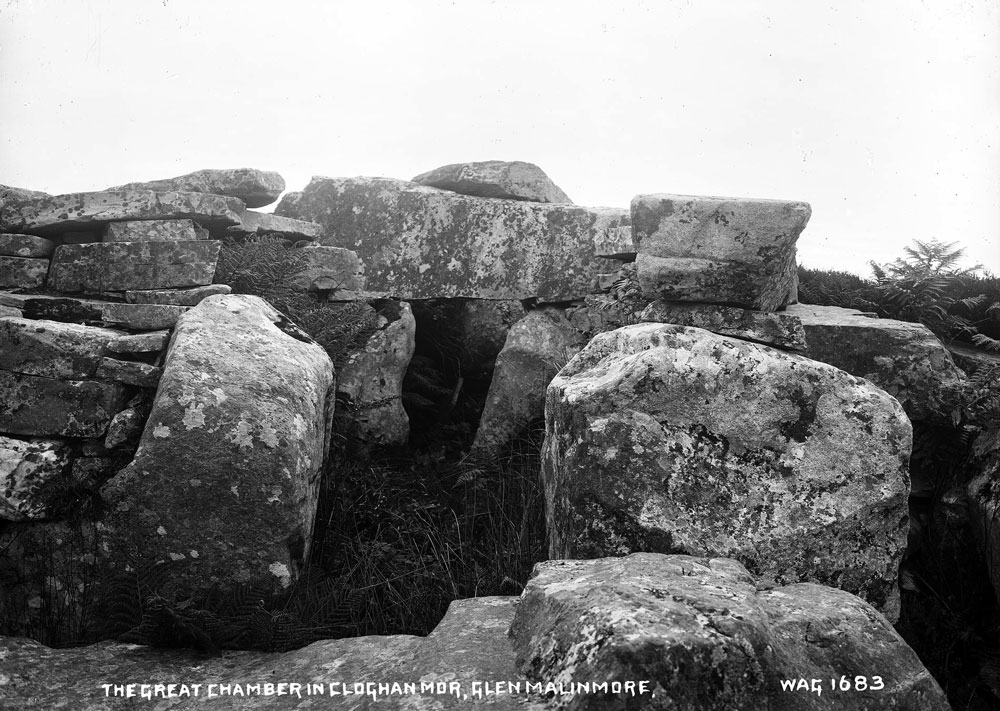

The Cloghanmore court cairn located at the centre of the Glencolumbkille peninsula is one of the finest and most accessible examples of an Irish monument of this kind. The monument has a huge court embraced by two large arms, each of which contains a small cist with megalithic art. The twin chambers face east, and the monument may be aligned to the equinox sunrises. One chamber still has it's flat lintel in position, the other, a large triangular stone has been pushed over and lies on the ground before the entrabce.

Photograph © National Museums of Northern Ireland.

This monument is one of the twelve largest and most complex examples of Irish court cairns, all of which are found around Donegal Bay, in Counties Mayo, Sligo and Donegal. There are several other fine examples of megalithic monuments in the area, including the Malinmore dolmens to the west, the massive central court cairn at Farranmacbride in Glencolumbkille, and the enormous portal dolmen at Kilclooney about twenty kilometers to the northeast. The large and impressive court cairns at Bavan (destroyed), Shalwy and Croaghbeg are on the coast to the south, and the superb examples of Creevykeel and Deerpark are located to the south across Donegal Bay in County Sligo.

There is a fine description of Cloghanmore and a virtual tour on the Voices From the Dawn website.

Description from the National Monuments Service

The monument, first shown on the 1848-50 edition of the OS 6-inch map, appears as 'Ruins of a Druidical Temple' on the pre-publication field map. It stands on generally level, grass-grown, boggy ground toward the head of the valley opening onto the north end of Malin Bay, 2.3 kilometers to the west. It is 50 meters south of the stream that flows westward along the valley and commands a good outlook toward the sea. The depth of bog in the immediate vicinity of the monument is at least 1 meter.

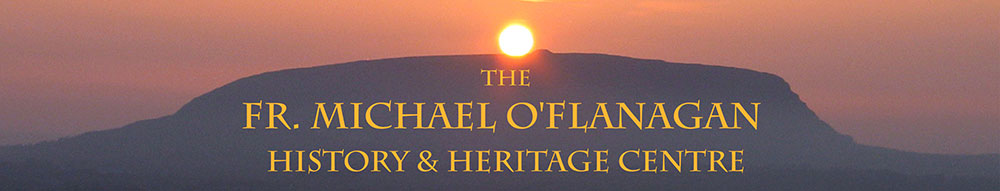

The monument, partly restored by the Board of Works toward the end of the 19th century, is in a fair state of preservation. Its orthostatic structure stands in a coffin-shaped cairn bounded by drystone walling. At the east, a short passage opens into a large, orthostatically defined full court of oval outline. Just inside the entrance passage a subsidiary chamber opens onto each arm of the court. The outer face of a court orthostat beside the entrance to each of these chambers bears picked motifs, apparently prehistoric in origin. Two galleries, parallel to each other and c. 1 meter apart, open off the western end of the court, and each is divided by jambs into two chambers.

The earliest available account of this monument is by Thomas Fagan, who saw it in 1847. Both he and Norman Moore, who visited here in 1871, found it difficult to interpret, perhaps because of its disordered state, and their reports are of limited value. Both included a rough sketch of the monument with their reports, but these cannot be reconciled either with each other or with the structure as now exposed. There are two useful illustrations of the monument before its restoration, both reproduced by Borlase (1897, 241). One is the plan published by Sir Samuel Ferguson. He visited the site in 1864, and the plan is thought to date to that year. The other, an undated and unattributed drawing showing a view of the monument from the front, was among a collection of drawings made available by Margaret Stokes to Borlase. Both illustrations are reproduced below. On Ferguson's plan cross-hatched areas seem intended to represent chambers, but set stones are not distinguished from displaced ones, and there is no indication of orientation. Nevertheless, as on the Stokes collection drawing, the main features of the monument can be recognised.

The involvement of the Board of Works at this tomb is referred to in the annual reports of that institution, but these contain practically no information about the nature of the work undertaken. One of the annual reports includes a description of the tomb, but this too contains little information, and the accompanying plan omits part of one of the galleries of the monument. This account does mention that 'the cells are being cleared out'. Work at the site seems to have been completed in 1887. However, a few years later unspecified work was carried out at a site identified only as 'Cloughan More'. It is not known whether this is the same site as that described here. Borlase, who visited the site in 1888, the year after its restoration, incorrectly assigned a north-south orientation to the main axis of the monument. He was informed that 'some few objects, such as pottery etc.' had been found by the workmen during the restoration.

Photograph © National Museums of Northern Ireland.

The precise nature and extent of the restoration work carried out by the Board of Works are not clear, but it appears from the available evidence, particularly the pre-restoration drawings, to have mainly involved removing cairn spill from the court, clearing the chambers, exposing the cairn outline and rebuilding the drystone kerb. This work would inevitably have entailed considerable archaeological loss.

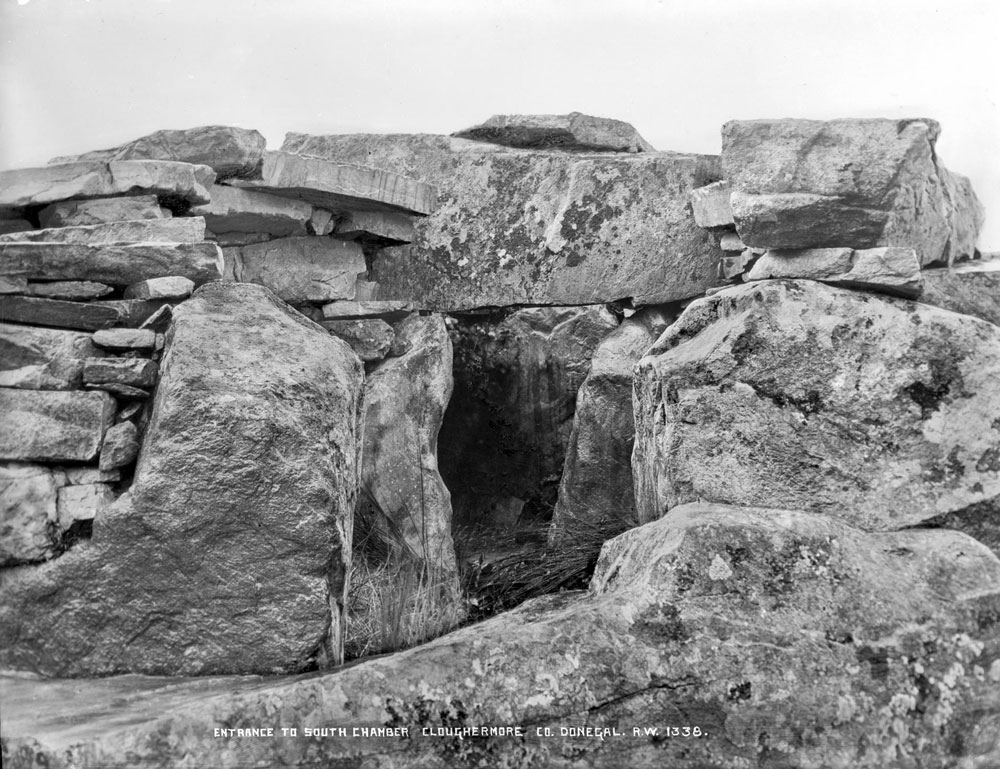

The cairn

The restored cairn is 46.3 meters long and attains its maximum width, 16.7 meters, midway along the court, from where it narrows to 12 meters at the east and 7.5 meters at the west. Its eastern half is 1-1.5 meters high. Toward the west and beyond the galleries it gradually declines by c. 1 meter in height. Rough grass now grows on its west end, which was bog grown until revealed during the restoration by the Board of Works. According to Borlase, the base of the drystone kerb was exposed by digging a trench around the monument. On the exposed base of the kerb, to judge from the denuded state of the front of the cairn as portrayed on the pre-restoration drawing from the Stokes collection, the Board of Works built a substantial 'wall' of dry stonework around the court. This rises above the court orthostats and is generally 2-2.5 meters thick but reaches 5.7 meters and 4.2 meters at the outer ends of the north and south sides of the monument.

It is clear that Thomas Newton Deane, then Superintendent of the Board of Works, believed that this monument was a cashel with 'cells' and not a chambered cairn. This must raise a question about the reliability of the shape of the restored cairn, which has been unfavourably commented on by Wakeman, 1890-91; Anon. 1890-91b. Only excavation could now determine this issue, but it is significant that its coffin-shaped outline has since found parallels at excavated monuments such as Behy and Shalwy. It would be expected, though, that cairn height would dip toward the court entrance, which is not the case here, and it is probable that the cairn at the front is built to a height greater than it is likely to have been in its original state.

The facade and entrance passage

The facade of the restored cairn is of drystone construction except for two orthostats, one at either side of the entrance passage to the court. It is considered that these may be in situ or at least restored to their original positions. Both are relatively low. The northern one is 0.35 meters high, and the southern one is 0.4 meters high.

Opposed orthostats form each side of the entrance passage, which is 3 meters long and 1.9-2.2 meters wide. The orthostat on the northern side is 1 meter high, and that at the south is 0.6 meters high. A displaced slab, 2 meters by 1 meter by 0.3 meters thick, leans against the northern orthostat. On Ferguson's (1879, 122) plan the space between the orthostats is cross-hatched, indicating that he may have considered this a chamber, an opinion shared by Borlase (1897, 243).

The court

The court is 16 meters long east to west and 12 meters wide. Court orthostats, their tops and outer faces hidden by the reconstructed cairn, survive along the full length of the south arm, except for short gaps, and there are two rather more substantial gaps in the north arm, one of 2.2 meters at around mid-length and one 4 meters long in its outer half. Nine stones survive along the north arm. They range from 0.9 meters to 1.75 meters long and from 0.2 meters to 1.5 meters high. There are seventeen stones along the south arm, 0.5-1.75 meters long and 0.2-1.1 meters high. The thicknesses of the courtstones cannot all be determined, but they seem to be 0.3 meters or more in most instances. In both arms the innermost stone is a tall one: that at the north is 1.5 meters high, and that at the south is 1.1 meters high at its inner end, sloping to 0.6 meters at its outer end. Beyond each there is a steady diminution in the heights of the courtstones to around midway along both arms, beyond which, with the exception of the stones fronting the subsidiary chambers, they vary from c. 0.2 meters to 0.5 meters high.

Apart from one or two taller ones at the inner end of the north arm, the courtstones do not appear to be represented on the two pre-restoration drawings of the monument. The annual reports of the Board of Works provide no information on the state of the court, but the occurrence of gaps between the orthostats indicates that, although fallen or leaning stones may have been re-erected as found, no attempt was made to replace missing ones. The cleared court is shown in a photograph from the Lawrence collection (c. 1880-1910).

In the inner half of the court are a number of displaced slabs. One of these, less than 1 meter from the front of the northern gallery, measures 1.6 meters by 1.15 meters and is 0.6 meters thick. To the south of this and just 0.3 meters from what may be a displaced lintel in front of the southern gallery there is another displaced slab, 1.1 meters by 0.75 meters and 0.35 meters thick. Approximately 2.3 meters east of the last is another, large one, 3 meters by 1.15 meters by 0.9 meters.

The northern subsidiary chamber

The northern subsidiary chamber has partly collapsed and lacks a backstone. Single orthostats form each side. The eastern one has fallen inward and leans against the western one. Both support an inclined roofstone. The orthostat at the west is 0.95 meters in exposed height. The eastern one would have stood c. 1 meter high when upright. The roofstone measures 2 meters by 1.45 meters and is 0.25 meters thick. Two court orthostats, not more than 0.1 meters apart, stand at the front of the chamber. The eastern one, one of the two decorated stones mentioned above, is 0.7 meters high. It rises 0.15 meters above the top of the western orthostat. This chamber can be recognised on the pre-restoration drawings. It appears to have been in much the same condition then as it is now.

Photograph © National Museums of Northern Ireland.

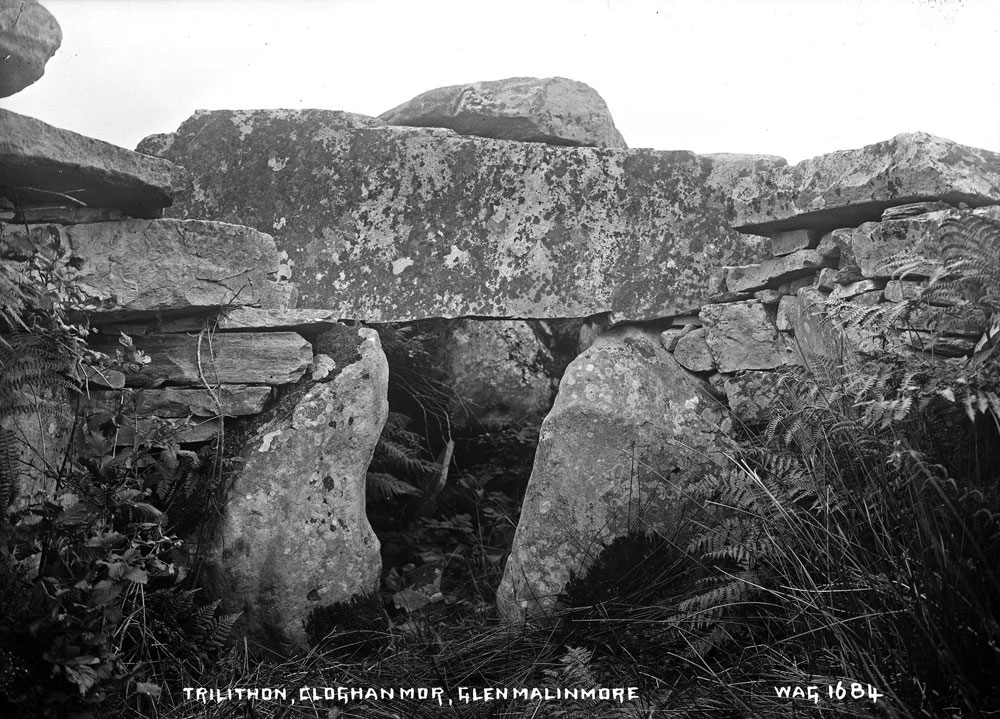

The southern subsidiary chamber

The southern subsidiary chamber is 2 meters long and 1.2-1.4 meters wide. A courtstone, split vertically into two pieces, stands at the entrance. This leans outward; it is 1.1 meters in overall length and 0.2 meters thick and would stand 1m high if upright. When in position this may have effectively blocked the entrance. The courtstone adjoining its inner end is the second of the decorated stones mentioned above. A displaced slab, 1.9 meters by 1.25 meters and 0.25 meters thick, leans against the split stone. Its original role is uncertain. Single orthostats that increase slightly in height toward the front form the sides of the chamber, and it is closed by a backstone between their ends.

A large thick slab laid flat between the sidestones forms the floor of the chamber. The flooring slab supports both sidestones. These are set outside it and lean inward against it. The backstone stands on top of the flooring slab. The northern sidestone, its inner end obscured by the cairn, is 1 meter high. The southern sidestone is 1.15 meters in greatest height. The backstone, slightly gabled in outline, is 1.15 meters high and rises 0.15-03 meters above the inner ends of the sidestones. The floor-slab covers the entire area of the chamber except for a small space in each rear angle. A small displaced slab, not on plan, lies in the southern rear angle. The inner end of the floor-slab is hidden by the backstone and cairn behind it. It is 1.35 meters wide, at least 1.8 meters long and at least 0.4 meters thick.

The massive floor-slab is an unusual feature, as is its relationship to the backstone, and in view of the restoration of the monument there must be a concern about the authenticity of the arrangement here. As both sidestones and the backstone are clearly identifiable on the pre-restoration drawing from the Stokes collection, it is hardly likely that the whole is a result of Board of Works restructuring. In regard to the relative positions of the backstone and floorstone, a possible parallel is suggested in an old report that claims that the sidestones of an unidentified chamber at Farranmacbride, when cleared, were found to rest on a 'basement slab'.